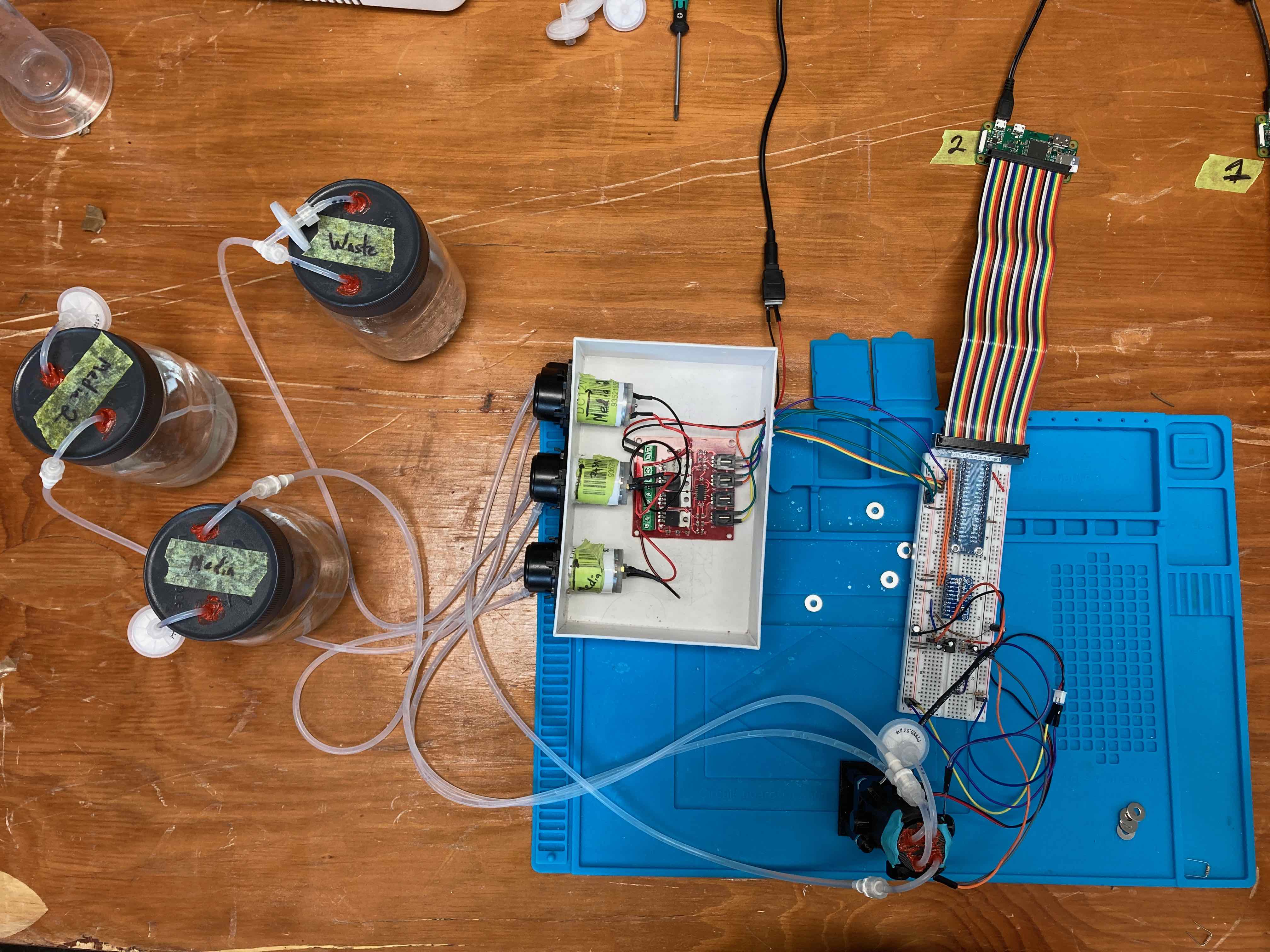

Let’s jump right into what even is a bioreactor. My friend Luiggi said it best: an example of a bioreactor is your sourdough starter. It’s full of microbes, you keep it protected from the elements, and periodically feed it. Brewing beer? Your fermenter is a bioreactor. Heck, your vegetable lacto-fermentations are bioreactors. But when I say “building a bioreactor”, I want to build a modular, computer controlled, and extensible bioreactor. Modular in the sense that pieces can be swapped out, and the bioreactor can be duplicated easily for higher throughput. A computer controlled bioreactor means that we can sleep at night and the bioreactor will still perform necessary operations. For this to work, we need to think about how to get digital measurements out of the reactor, and then translate those measurements into automatic actions. Finally, extensible refers to the ability to for the bioreactor to be applicable for many use-cases. I want to be able to solve many things with this bioreactor. There’s one more thing I’d like: cheap. Well, relatively cheap. Professional bioreactors, even the smaller ones, can cost thousands of dollars. Let’s build one for a few hundred dollars. At the end of this blog post series, we’ll have something that looks like this:

May look complicated now, but we’ll go through each piece over this series

May look complicated now, but we’ll go through each piece over this series

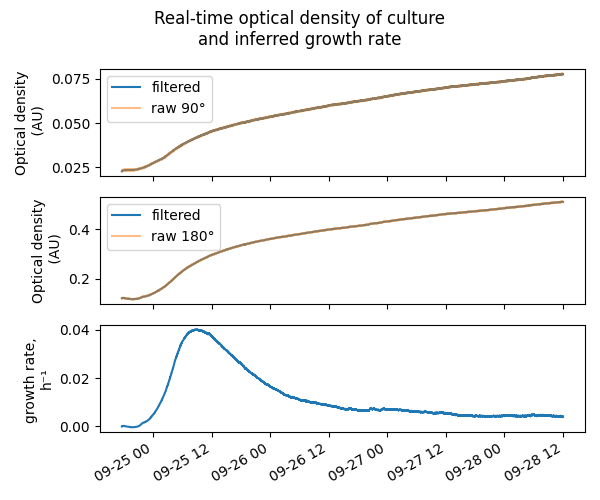

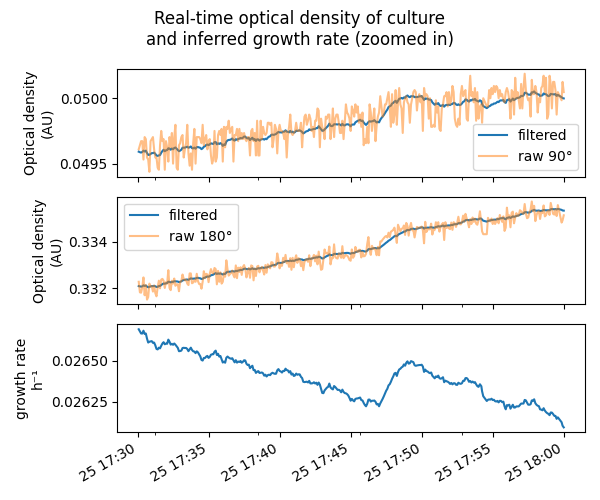

We’ll be able to track real-time growth of our cultures too:

Later blog posts will explain the electronics and math behind this

Later blog posts will explain the electronics and math behind this

Wait - why do I want to build a bioreactor?

While there a many uses of a bioreactor, our goal is going to be a technique called lab directed evolution, which is the microbial equivalent of artificial selection. Artificial selection has been applied to organisms around us for thousands of years. We have selectively bred plants like corn into the enormous monsters they are today (see image below). Likewise for livestock and dogs. Interestingly, we have also artificially selected some microbes too: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, aka brewers and bakers yeast, is very specialized today due to human intervention. Likewise, Aspergillus oryzae’s, aka koji, use to be toxic to humans, but we’ve selected the toxicity out.

Corn over time. Source: Doebley, J., https://teosinte.wisc.edu/images.html

Corn over time. Source: Doebley, J., https://teosinte.wisc.edu/images.html

Today, lab directed evolution is a tool used in modern microbiology. Importantly, because of the extremely short generation time of microbes, evolution occurs on the order of days to weeks (vs centuries for plants and animals). The engineers of lab directed evolution have a specific goal in mind, expressed as the phenotype of the organism, and they reverse engineer what the environment should look like to reach that goal. For example, if the desired phenotype is heat tolerance, the engineers will slowly expose the microbes to higher and higher temperatures: the microbes that happen to be more heat tolerant will survive more often and continue to reproduce. However, if the engineers are not careful, they will inadvertently select for other traits too. Consider that the microbes are always competing for nutrients as well, and very quickly the initial nutrients will be consumed and the microbes will enter their stationary phase. So in the above scheme, if they only raised the temperature slowly over time, they would select for both heat tolerance and ability to survive well in the stationary phase. This may not be what is wanted. Instead, the culture is kept at a constant cell density. This is typically a density where there is an abundance of nutrients for each microbe, so no selection occurs in this dimension (that’s a lie: there is always a selection for increasing growth rate). To accomplish a constant cell density, periodically a small amount of liquid is removed and replaced by new media. Tuned correctly, this keeps the volume constant and the culture at a constant density.

An important point is that lab directed evolution is not rational design - the engineers don’t care about the mechanisms of heat tolerance (yet), but they are allowing random gene-flipping plus selection to find a solution. Rational design would be something like finding a heat-tolerant phenotype in another organism, translating that into DNA, and inserting the DNA into the microbe. Sometimes, the rational design path is too complicated or difficult, and lab directed evolution feels like cheating. Directed evolution does the exploration (sheer population size) and exploitation (selective pressure) for us! On the other hand, often the rational design is sometimes easier: evolving a brand new enzyme has about 0 probability of occurring in a person’s lifetime, but adding the enzyme’s DNA to a microbe can be trivial. So both lab directed evolution and rational design are tools, and not replacements of each other.

Finally, my interest in lab directed evolution is that it is just so much in the spirit of “Controlled Mold” - literally controlling the phenotype of the mold! In the list below are some examples, including with molds, of more lab directed evolution applications:

Applications of lab directed evolution

I’ve been collecting the really cool uses of lab directed evolution, and use these as motivation:

- Evolving a traditional brewer’s yeast to thrive in new brewing environments. New environments for brewer’s yeast could be higher/lower temperature, higher (alcohol, IBU, caffeine), concentration, lower pH, salt %.

- Yeast can only ferment a short list of carbohydrates. By slowly depleting yeast’s traditional carbon sources, it forces the yeast to adapt to new carbon sources, like lactose. See [Attfield, 2006]

- Similarly, filamentous fungi can be evolved to consume new carbon sources, like raffinose, a sugar which is a cause of digestive discomfort after eating soybean tempeh.

- Lactobacillus, used in sour beer production, can be evolved to be more alcohol, pH, or IBU tolerant.

- Some algae are facultative heterotrophs. Directed evolution can be used to evolve a stronger and faster heterotrophic metabolism.

- Triton Algae Innovations has used directed evolution to evolve heme in algae. They accelerated the process by flashing the microbes with UV light which caused a higher mutation rate.

- Algae can be evolved to produce more carotenoids by changing the light conditions, see [Fu, 2013]

- Improving yeast culture density, as demonstrated in [Wong, 2018]

- Improving growth rates after rational design. When modifying the genes of a microorganism though modern genetic engineering, the growth rate is typically lowered due to new proteins or metabolites being constructed. By subjecting the organism to an environment with abundant nutrients, over time, the population will evolve to increase its growth rate.

- Improving metabolite production after rational design. After adding the genes of carotenoid production to yeast but wanting a higher yield, [Reyes, 2013] exploited the antioxidant of carotenoids. They exposed the yeast to high levels of hydrogen peroxide. The yeast evolved to counteract the hydrogen peroxide by producing more carotenoids.

- The original inventors of the morbidostat [Toprak, 2013] were interested in antibiotic resistance in bacteria. They subjected E. coli to a slowly increasing level of antibiotics, and after two weeks, the bacteria had grown resistance to the highest antibiotic concentration in their experiment design.

- In [Ekkers, 2020], the authors hint at evolving an anticipatory response. Amazing!

Back to the bioreactor

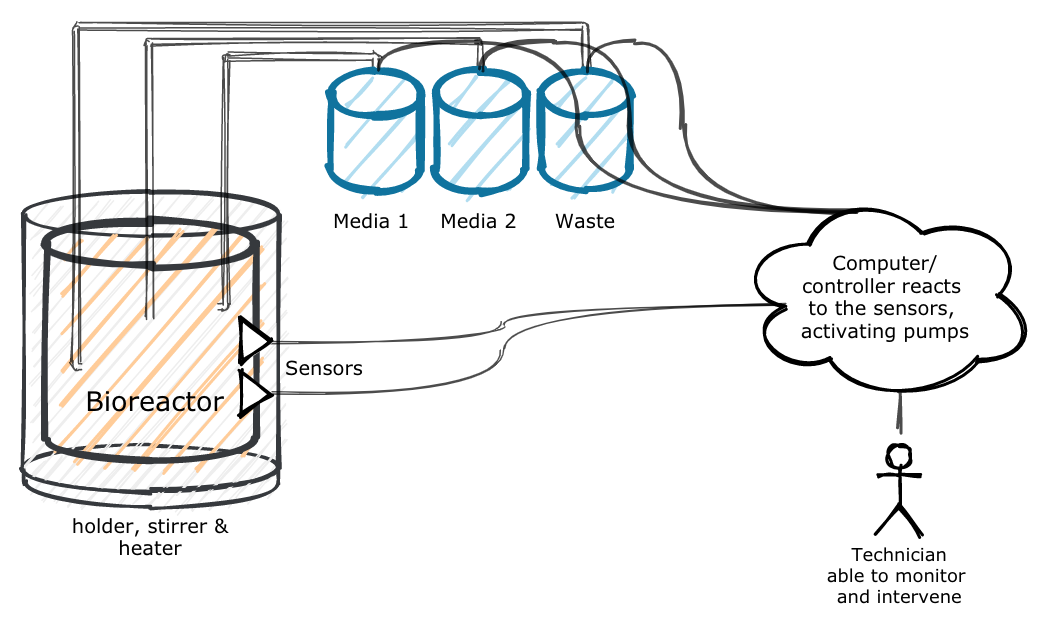

To build a our bioreactor, we will need the following:

- autoclavable vials

- sensors to read measurements from our bioreactor

- A holder for the vial and sensors

- a computer loaded with software to control the input/output of the pumps

- Pumps to remove liquid and add new media.

Graphically, it looks something like this:

In the next blog post, we’ll look at the first part of this construction: the holder and associated sensors.

References

- Toprak, E., Veres, A., Yildiz, S. et al. Building a morbidostat: an automated continuous-culture device for studying bacterial drug resistance under dynamically sustained drug inhibition. Nat Protoc 8, 555–567 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.021

- A low-cost, open source, self-contained bacterial EVolutionary biorEactor (EVE) Vishhvaan Gopalakrishnan, Nikhil P. Krishnan, Erin McClure, Julia Pelesko, Dena Crozier, Drew F.K. Williamson, Nathan Webster, Daniel Ecker, Daniel Nichol, Jacob G Scott bioRxiv 729434; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/729434

- A user-friendly, low-cost turbidostat with versatile growth rate estimation based on an extended Kalman filter Hoffmann SA, Wohltat C, Müller KM, Arndt KM (2017) A user-friendly, low-cost turbidostat with versatile growth rate estimation based on an extended Kalman filter. PLOS ONE 12(7): e0181923. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181923

- Wong, B., Mancuso, C., Kiriakov, S. et al. Precise, automated control of conditions for high-throughput growth of yeast and bacteria with eVOLVER. Nat Biotechnol 36, 614–623 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4151

- Ekkers, DM, Branco dos Santos, F, Mallon, CA, Bruggeman, F, van Doorn, GS. The omnistat: A flexible continuous‐culture system for prolonged experimental evolution. Methods Ecol Evol. 2020; 11: 932– 942. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13403

- Improving carotenoids production in yeast via adaptive laboratory evolution

- Fu W, Guethmundsson O, Paglia G, Herjolfsson G, Andresson OS, Palsson BO, et al. 2013. Enhancement of carotenoid biosynthesis in the green microalga Dunaliella salina with light-emitting diodes and adaptive laboratory evolution. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97: 2395-2403.

- Attfield PV Bell PJL (2006) Use of population genetics to derive nonrecombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that grow using xylose as a sole carbon source. FEMS Yeast Res6: 862–868.

Cameron Davidson-Pilon

Cameron Davidson-Pilon