I always wondered if researchers had played around with koji growing parameters - turns out they have, and with a great level of detail in numerous studies. This post will be the first of a few going over these studies - starting with temperature, water content, and polishing rate.

Overview

Koji-making is all about optimizing growth conditions for the specific application you’re after. Although koji-makers had centuries of knowledge about optimal growth conditions, it wasn’t examined scientifically until the 20th century.

Everything in this post comes from the Brewing Society of Japan, and its academic journal (which has been running from 1906 to today) - more on that at the end of the post. The experiments below were run mostly in the the 1970s and the 1980s by researchers looking to explain and quantify different aspects of koji-making.

Temperature

One of the most obvious parameters that researchers tested was the cultivation temperature. The growth of A. oryzae on white rice was tested at temperatures between 30°C and 40°C. Of course, the researchers know that growing koji for a fixed time at different temperatures would not be a fair comparison: at different temperatures, the koji’s growth rate (μ, measured in h-1) is different, and hence enzyme production is different. Thus, enzyme production was compared at two points different points:

- When the koji consumes 10mL oxygen per gram of koji (dry weight basis), and;

- When the koji reaches a maximum cell mass

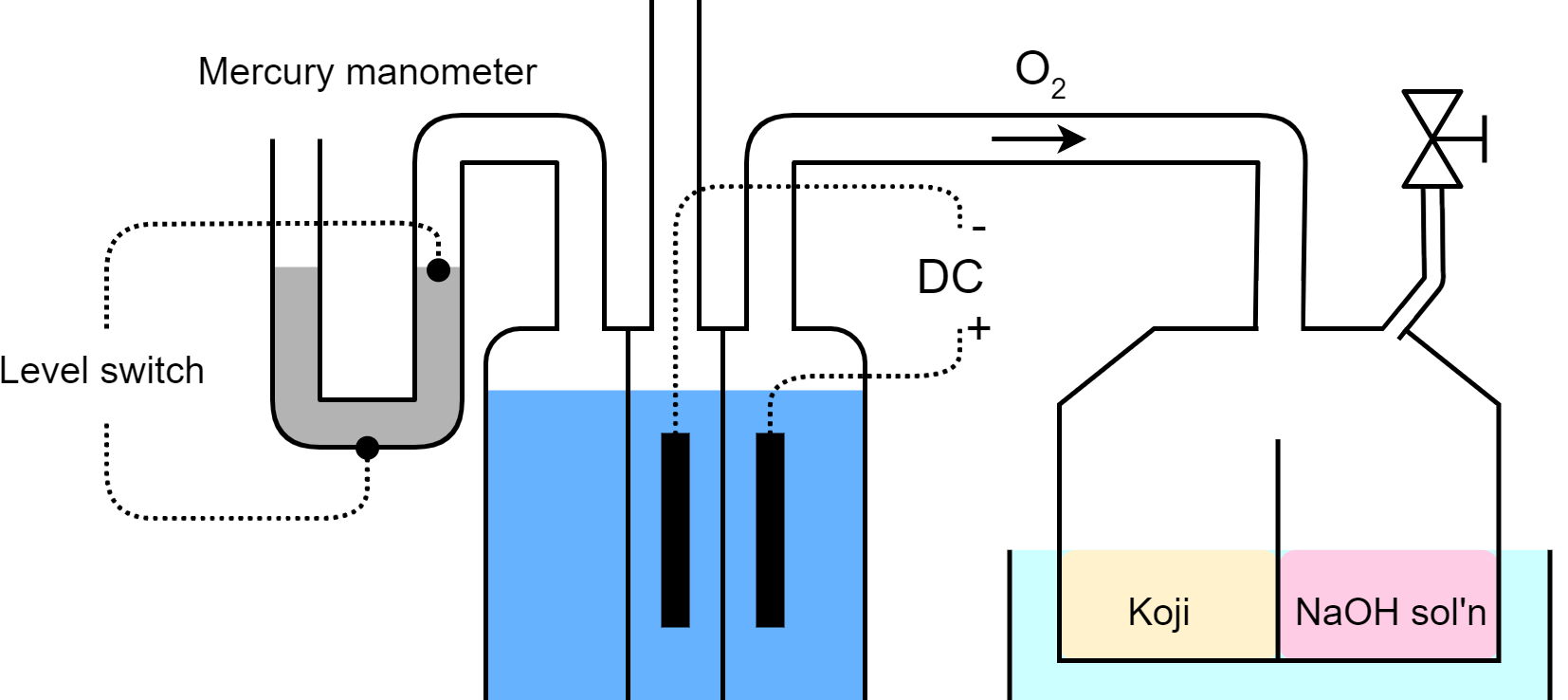

Effect of culture temperature on enzyme production ([1] - 10mL O2 consumed/ g koji and [2] at maximum cell mass). Units are arbitrary, but higher values imply more activity in the assay.

Effect of culture temperature on enzyme production ([1] - 10mL O2 consumed/ g koji and [2] at maximum cell mass). Units are arbitrary, but higher values imply more activity in the assay.

Conclusion: in general, higher temperatures favour amylases, and lower temperatures favour proteases and peptidases.

In practice, no koji makers would set a single temperature for their koji for the entire duration of its growth. The above temperatures are mostly important during the last 12 hours of growth when the mycelium is producing the most enzymes.

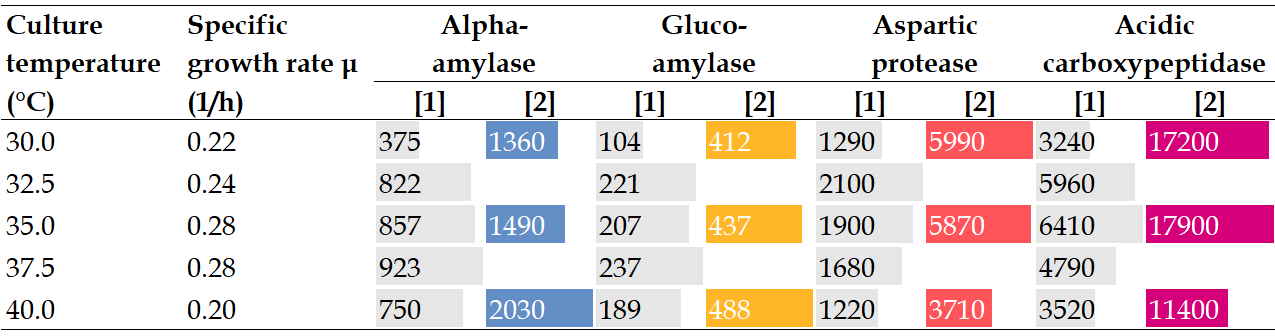

As an aside, this was the experimental set-up:

The experimental setup - see Ref. 2

The experimental setup - see Ref. 2

Water content

Another parameter they tested is the steamed rice water absorption rate, which is defined as follows:

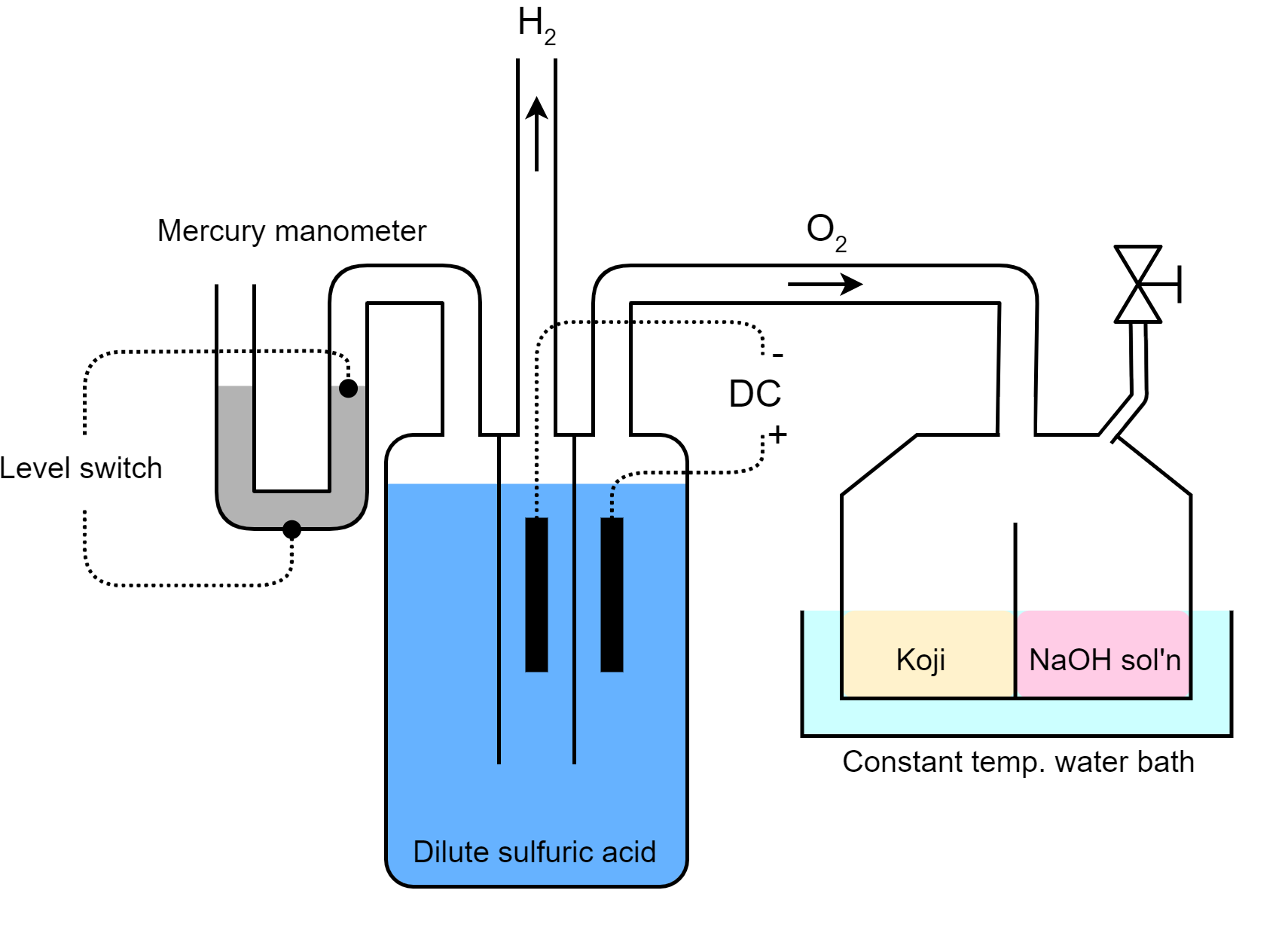

\[\text{Steamed rice water absorption rate (%)} = \frac{\text{Steamed rice weight} - \text{Dry rice weight}}{\text{Dry rice weight} } \times 100\%\]Note that this is NOT the same as total water content, since the dry white rice also contains a small amount of water (around 15% by weight). The term “dry rice weight” here is a bit of a misnomer - it’s the weight of uncooked, unsoaked rice. When varying the steamed rice water absorption rate from 24 - 51%, this is what they found:

Effect of water absorption rate on enzyme activity

Effect of water absorption rate on enzyme activity

The researchers used the same metric above, and pulled the koji once it had consumed 10mL oxygen / g koji for a fair comparison. Here, the total culture time is an indicator of growth rate: the shorter the culture time, the faster the growth rate.

Conclusion: although wetter rice will grow koji faster, it yields less enzymes in total (both amylase and proteases).

Koji makers already knew that overly wet rice yielded weak koji. Another researcher found that wet rice lead to the over-accumulation of glucose, which inhibits enzyme production. In practice, the water content actually changes throughout the koji production period as some of the water vapour is released from the rice. Typical operations start at 35-40% steamed rice water absorption rate, and finish at 24 - 28% (mirin) down to 17-19% (sake).

Polishing rate

Yet another parameter that was tested is the polishing rate, which is defined as follows:

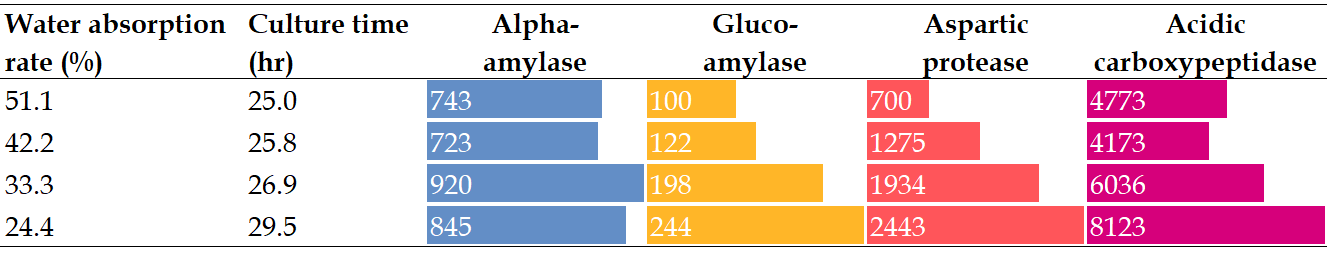

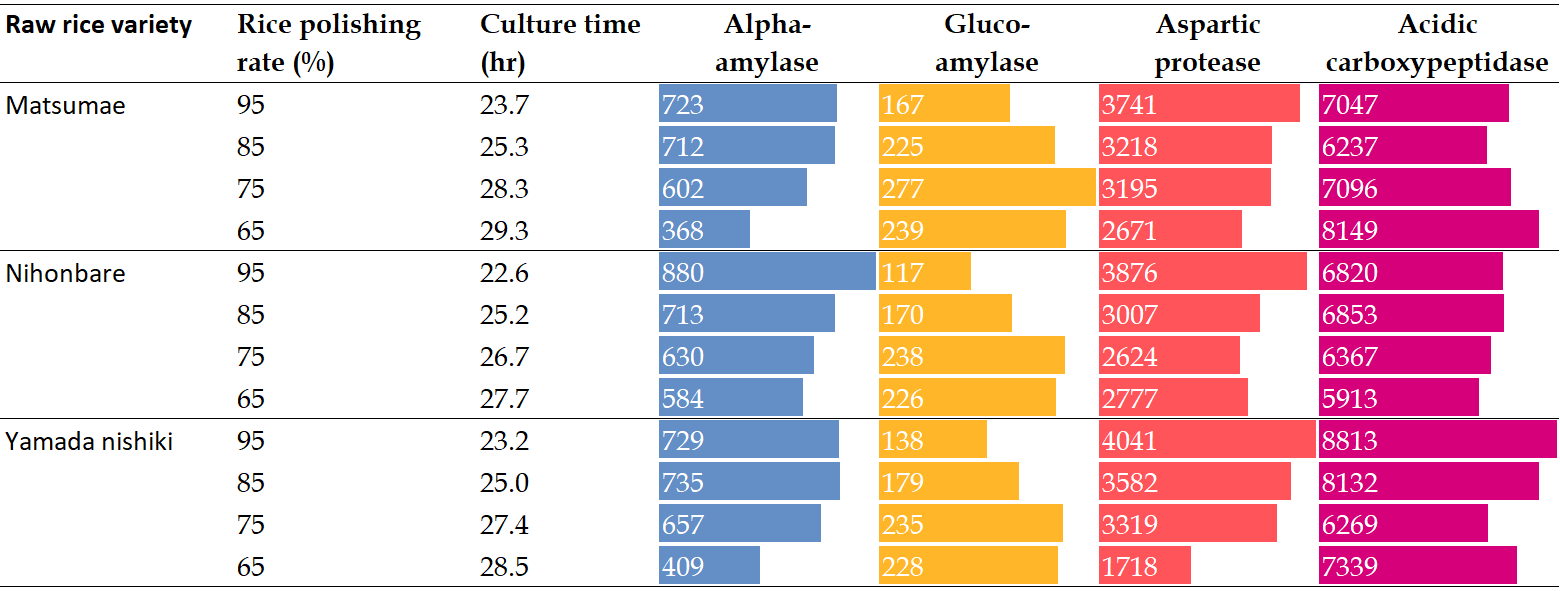

\[\text{Polishing rate (%)} = \frac{ \text{Weight of white (polished) rice}}{\text{Weight of brown rice}} \times 100\%\]Although a bit counter-intuitive, a lower polishing rate means more of the rice is removed. Polishing rates were varied from 65% - 95% on three varieties of rice.

Effect of polishing rate on enzyme activity

Effect of polishing rate on enzyme activity

Again, the koji was pulled once it had consumed 10mL oxygen / g koji.

Conclusion: rice variety doesn’t matter much - and enzyme yields are mixed. Rice with a high polishing rate, which contains more nutrients, grows koji faster. Rice with a low polishing rate, which is mostly starch, grows slower.

In practice, miso and mirin typically use rice with a high polishing rate. Rice with lower polishing rates are reserved for higher and higher grades of sake - where depriving the sake mash of nutrients yields sake with a clean, refined taste.

Other effects

There are of course, many more parameters that were tested. Here are some of them:

- Carbon dioxide

- Oxygen

- Air humidity

- Inoculation rate

- The addition of salts & minerals

This last one, the addition of salts & minerals, is really interesting and needs another post. As for the other four, in short - they don’t significantly affect koji quality within practical bounds. If there’s enough interest, I’ll look at them in detail.

Conclusions

Notes

I’ve omitted units for enzyme activity, which are described in the paper, along with the experimental setup and methodology. I’ve also omitted results for Tyrosinase and Deferriferrichrysin, which were also measured in these studies.

The Brewing Society of Japan

A quick footnote: a lot of the information in this post comes from the Brewing Society of Japan, which was established in 1906. Their articles are availble on J-Stage. There are also a other useful journals like the Journal of Japanese Society of Food Science and Engineering.

For the Brewing Society of Japan, they also have a Bookstore, and the books help distill all the information from the Journal. Notable titles are Koji Studies「麹学」and Molecular Koji-kin Studies 「分子麹菌学」

I’m trying to translate as much these as I can, but if you’re interested, message me on twitter @Keeifa

Additional reading

Rice polishing ratio, explained by Nada-ken

References

Murakami Hideya. Koji Studies - 6th edition. Chapter 5 - Koji Enzymes. The Brewing Society of Japan: Tokyo, 2018.

Naoto Okazaki et al. Effects of koji-making conditions on growth and enzyme production. Journal of The Brewing Society of Japan, 74:10 (1979), 683-686, https://doi.org/10.6013/jbrewsocjapan1915.74.683

Keith Wong

Keith Wong