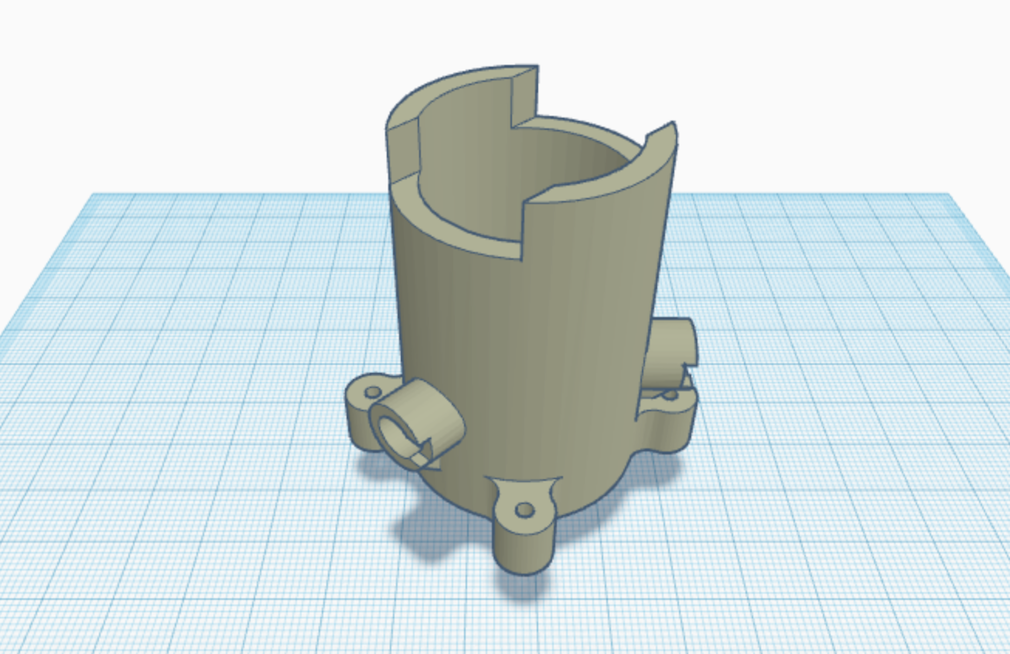

The first part of building our bioreactor will focus on the container for the glass vial. The original designs for this are from another open-source project (and research article), “A low-cost, open source, self-contained bacterial EVolutionary biorEactor (EVE)”. 3D sketch below!

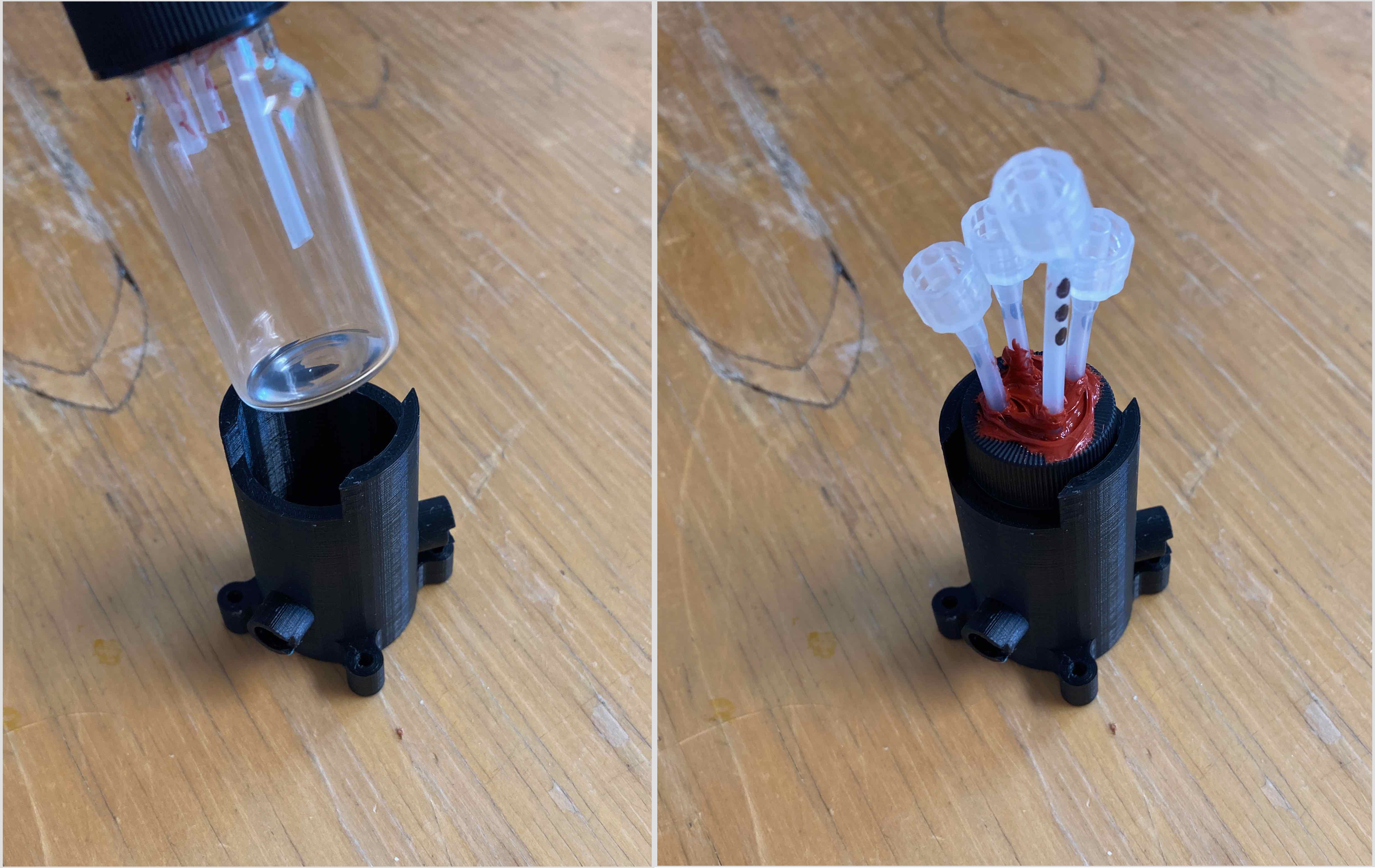

We’ve made some changes to it, which I’ll get to later. For now, I want to explain the mechanism of how it works. A 20ml vial fits snuggle in the center:

The holes, angled at 135° from each other, are designed to fit LEDs and a cap goes over the exposed end.

What LEDs though? In one hole, we fit an infrared (IR) LED, and in the other hole we fit an infrared photodiode. The latter is a component that produces a current when IR light hits it. This is how we will measure the turbidity (the cloudiness) of the solution, which is a measure of cell density!

The theory is that cells will scatter the IR light off their surfaces and more cells ⇒ more scatter ⇒ more light picked up by the photodiode. In fact, the relationship is linear (up to a limit), so current produced should be proportional to cell density. Later, in another article, we will learn how to translate that current into a computer readable signal.

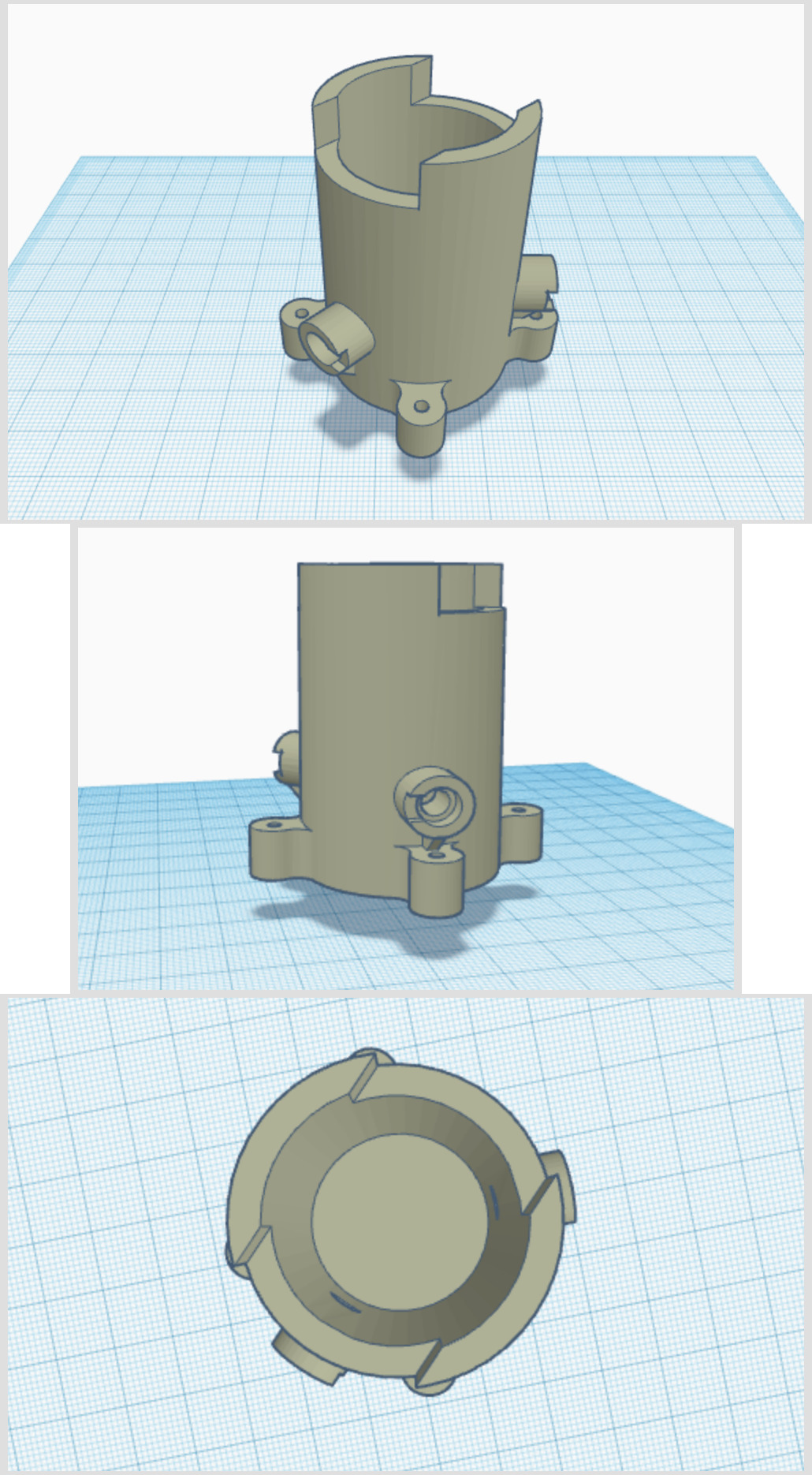

It’s great that we can measure cell density, but what if we also wanted to build a photobioreactor? That is, what if we wanted to add LEDs that phototrophic algae could feed off of? Similarly, what if we wanted to introduce UV light into the culture, to induce higher rates of mutation in the organims? Furthermore, if we have more IR photodiodes, we could get better statistical estimates in our inference pipeline. Introducing our new vessel:

Yes, this has been printed and is running now. 3D printer schematics available here

Yes, this has been printed and is running now. 3D printer schematics available here

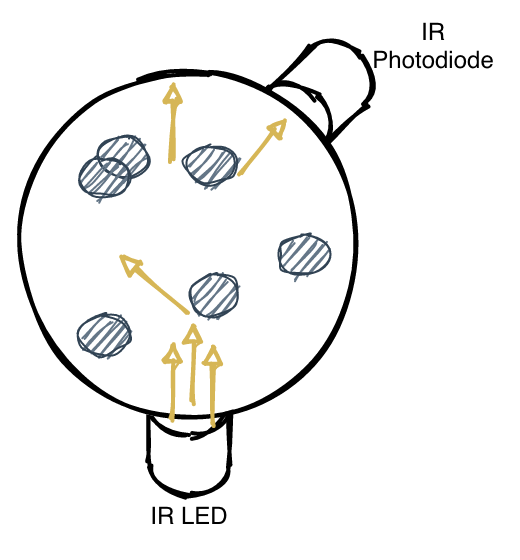

This has six LED holders for all the applications listed above. In the image below, we show off the application of 4 photodiodes (at 180°, 135°, 90° and 45°) and a UV LED.

.png)

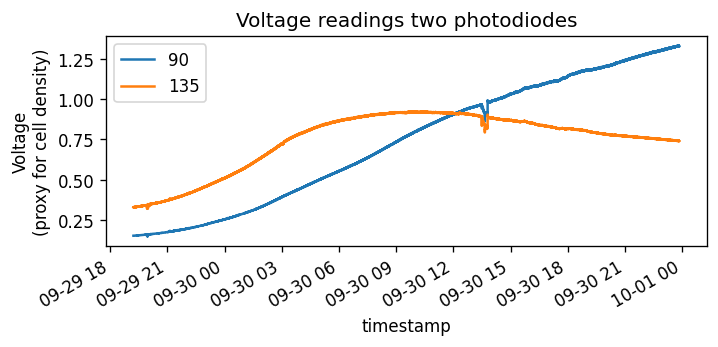

The different angles have different uses: the 180° can measure absorbance, and the others can measure scatter. The 135° has the strongest signal (due to the most scattering in that direction), however has the lowest saturation (too many cells ⇒ too much turbidity ⇒ loss of signal). The 90° and 45° photodiodes have a weaker signal, but will work better in high-turbidity environments. This really matters: take a look at the following data:

*The growth curves respresented by a 135° sensor and a 90° sensor. The 135° sensor saturates quicker due to high turbidity. The noise at 16hours in was caused by me playing with wires. *

*The growth curves respresented by a 135° sensor and a 90° sensor. The 135° sensor saturates quicker due to high turbidity. The noise at 16hours in was caused by me playing with wires. *

Both start off with the same pattern: exponential growth, but the 135° photodiode tapers off more quickly, while the 90° photodiode continues to grow and exhibit a more “classic” growth curve.

Magnetic stirring

Below each holder is a stand with a small 40mm DC fan. Attached to to the fan blades are two small magnets. When the fan is turned on, the magnets spin a corresponding stir bar in the vial above. he fan is powered by a MOSFET, and the speed is controlled by a pulse-width-modulation signal from a RaspberryPi. More on that in a future article!

slow-motion video of our magnets and fan

slow-motion video of our magnets and fan

Cameron Davidson-Pilon

Cameron Davidson-Pilon