What if you could make food out of just basic chemicals and microbes? At a first glance, this seems like a great idea since microrganisms grow quickly, are thermodynamically efficient, and can add value to low-cost chemicals and waste streams.

This concept, which gained a lot of traction in the 1960s and 1970s, is called “Single Cell Protein (SCP)”, in which a microbe (usually fungi, bacteria, or algae) is cultured for direct consumption. Although “microbial biomass” might be a more accurate term, we’ll continue to use the term SCP.

This post is about one SCP product: Quorn - which is the brand name for imitation meats based on cultured Fusarium venenatum, a soil mold that has become one of a few successful SCP products to date. And while far from perfect, it’s still a fascinating story.

The Inception of Quorn and the ‘Protein Crisis’

Between the 1950s and 1970s, amidst a massive global population boom, there was a concern that children in developing countries were becoming malnourished due to a lack of protein. This culminated in a 1968 paper from the United Nations with policies to avert this ‘protein crisis’, and one of their recommendations was to promote the development of single-cell protein for direct consumption or animal feeding [1]. This sounds promising at first: microorganisms grow fast, don’t take up a lot of space, and are 30% - 80% protein by dry mass. [2]

Around 1967, the British company Rank Hovis McDougall (RHM) took on the challenge, eventually selecting a strain of Fusarium venenatum (A 3/5) out of 3000+ candidates. To scale-up, RHM initially worked with DuPont using continuously stirred tank reactors (CSTRs) before collaborating with the Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) to use their airlift bioreactor - more on that later [3]. This joint venture would be known as Marlow Foods.

There are plenty of articles highlighting the history of Quorn, which I’ve linked in the References section. Although the history and biology of Quorn is interesting, I want to focus on two things in this post:

- How did Quorn succeed at scale, from an engineering perspective?

- What did Quorn actually accomplish?

Bioreactor Design - Upstream Processing

Growing F. venenatum in a liquid culture is fairly straightforward. Like other liquid cultures, the fungi can be propogated in a sterile culture of carbohydrates, ammonia, oxygen, and nutrients: yielding biomass and carbon dioxide.

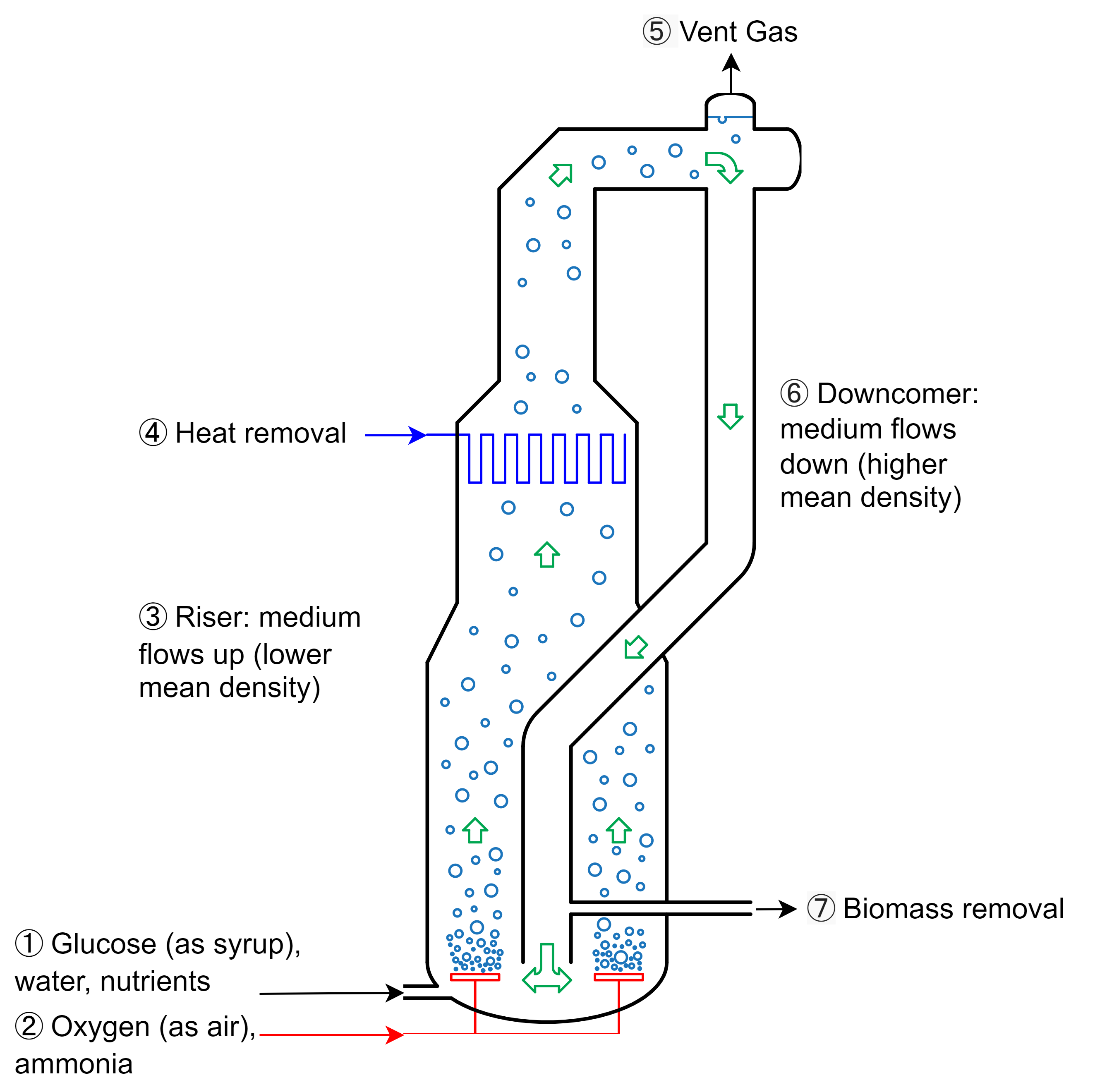

This can be accomplished with any bioreactor design, but after two iterations, the design team eventually opted for an external-loop airlift bioreactor [4-7] that looks a bit like a Klein bottle from mathematics:

Here’s how it works:

- Sterile water, carbohydrates (as syrup or molasses), and nutrients are pumped into the bottom of the bioreactor

- Sterile oxygen (as air) and a nitrogen source (ammonia) are bubbled into the bottom of the bioreactor

- The aerated mixture rises due to its lower average density

- Metabolic heat is removed using cooling water coils

- Waste carbon dioxide and gases are vented at the top of the bioreactor

- The culture broth, now with a compartively higher average density, drops into the downcomer

- A portion of the biomass is harvested and the remainder returns to the bottom of the bioreactor to repeat the cycle

As a side-note, the bioreactor design shown above is based off of Quorn-2 and Quorn-3, Marlow Foods’ second and third bioreactor, respectively. The first pilot bioreactor, Quorn-1, was initially used to develop ICI’s Pruteen™ - a bacterial SCP meant for livestock - and looks a bit different. Quorn-2 and Quorn-3, at 150,000L, are the biggest bioreactors of their type.

This is a great design for several reasons:

- At the physical scale Quorn is dealing with, the design is more efficient AND gentler than CSTRs, whose rotating blades would damage the growing hyphae. Mixing by aeration only is gentle and suitable for viscous broths with lots of hyphae.

- The loop design avoids short-circuiting of fresh carbohydrates and nitrogen from the inlet directly to the outlet, which can occur in conventional CSTRs.

- Adding air to the bottom of a tall bioreactor allows oxygen to dissolve quickly into the media through the immense hydrostatic pressure

The bioreactor is operated continuously, typically for several weeks before resetting the bioreactor (for reasons discussed later). Continuously operated bioreactors will always be more productive than batch bioreactors because they maintain a high biomass concentration at all times.

Quorn Quirks - Downstream Processing

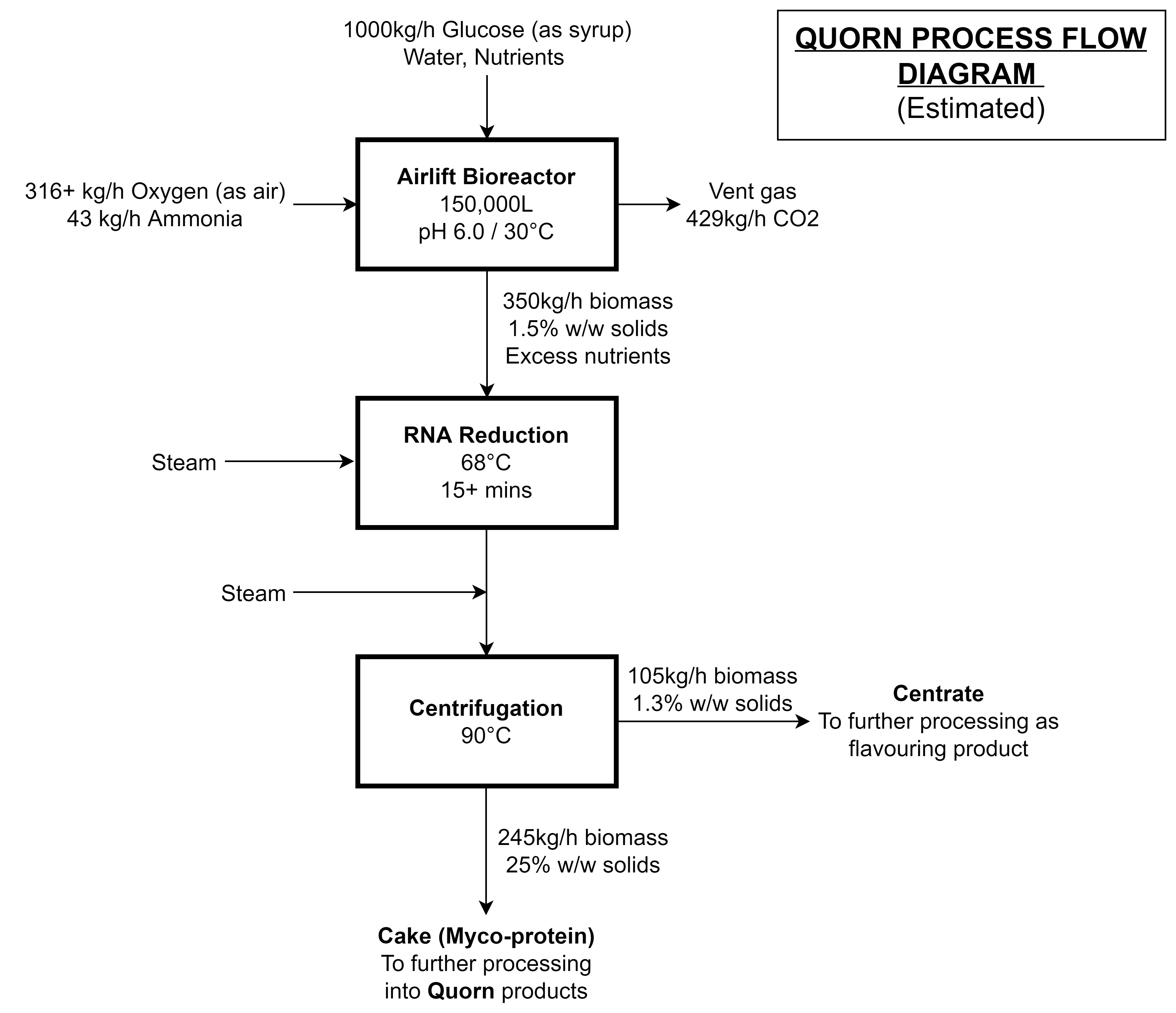

If everything’s gone well, coming out of our bioreactor is a solution of hyphae and spent substrate that’s around 1.5% biomass by weight. A few downstream processing steps are required before the biomass is converted to Quorn mycoprotein.

Nucleic Acids

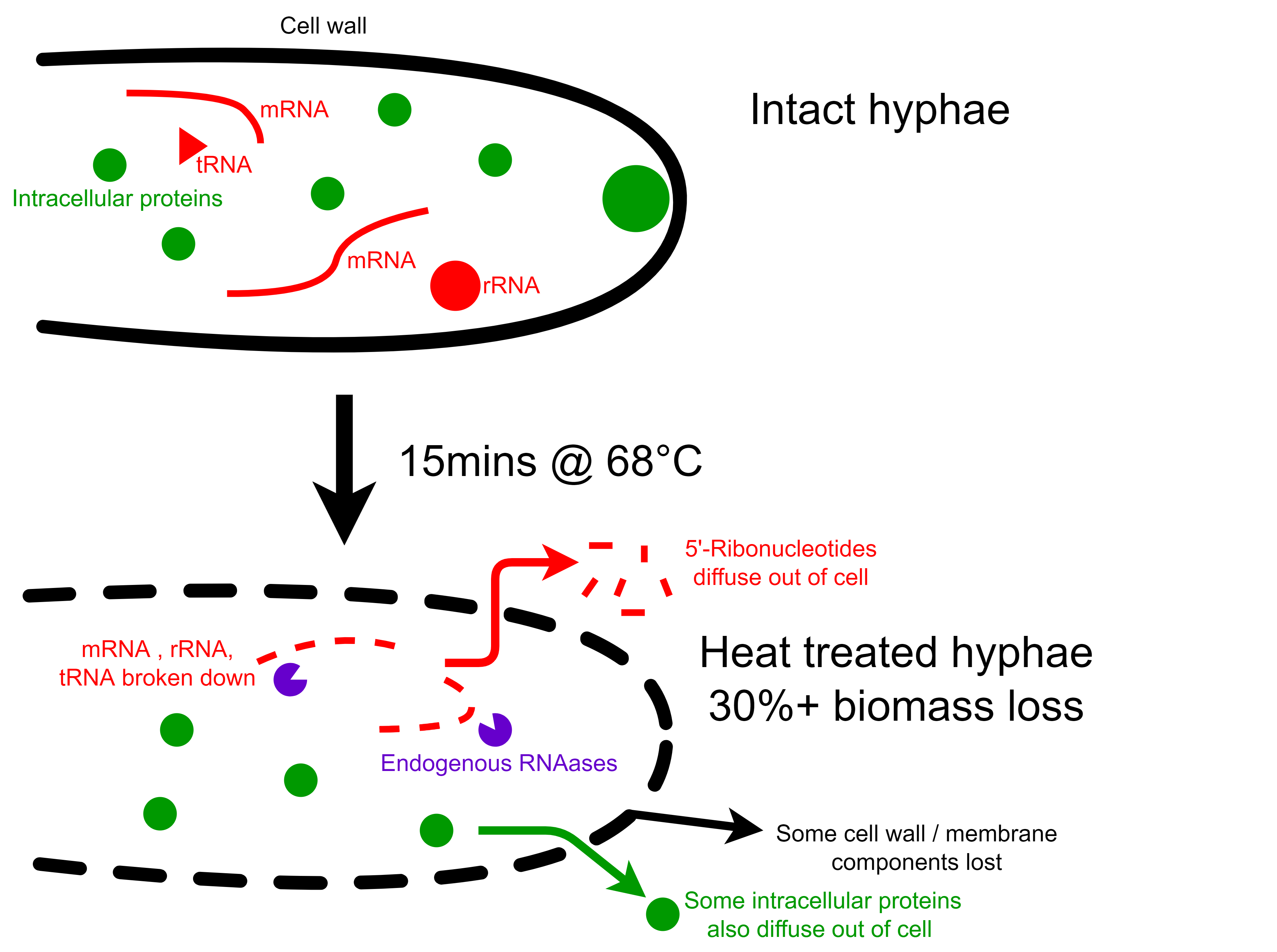

Things that grow fast and produce proteins quickly contain a lot of RNA for translation. This is a problem because humans metabolize RNA into uric acid and orotic acid, and the overaccumulation these can lead to gout and liver damage, respectively.

The F. venenatum biomass has a nucleic acid content of around 8-9% w/w dry basis which is too high for human consumption. To solve this problem, the biomass is heated to 68°C for 15+ minutes, and endogenous RNAases break down cellular RNA into 5’-ribonucleotides, which diffuse out of the cell. This heating process causes some components of the hyphae to leak out into the surroundings - and up 30% of the biomass is also lost in the process.

Luckily, some 5’-ribonucleotides are potent umami compounds and synergistic with glutamate. The producers of Quorn concentrate this liquid and sell it as a flavour enhancer.

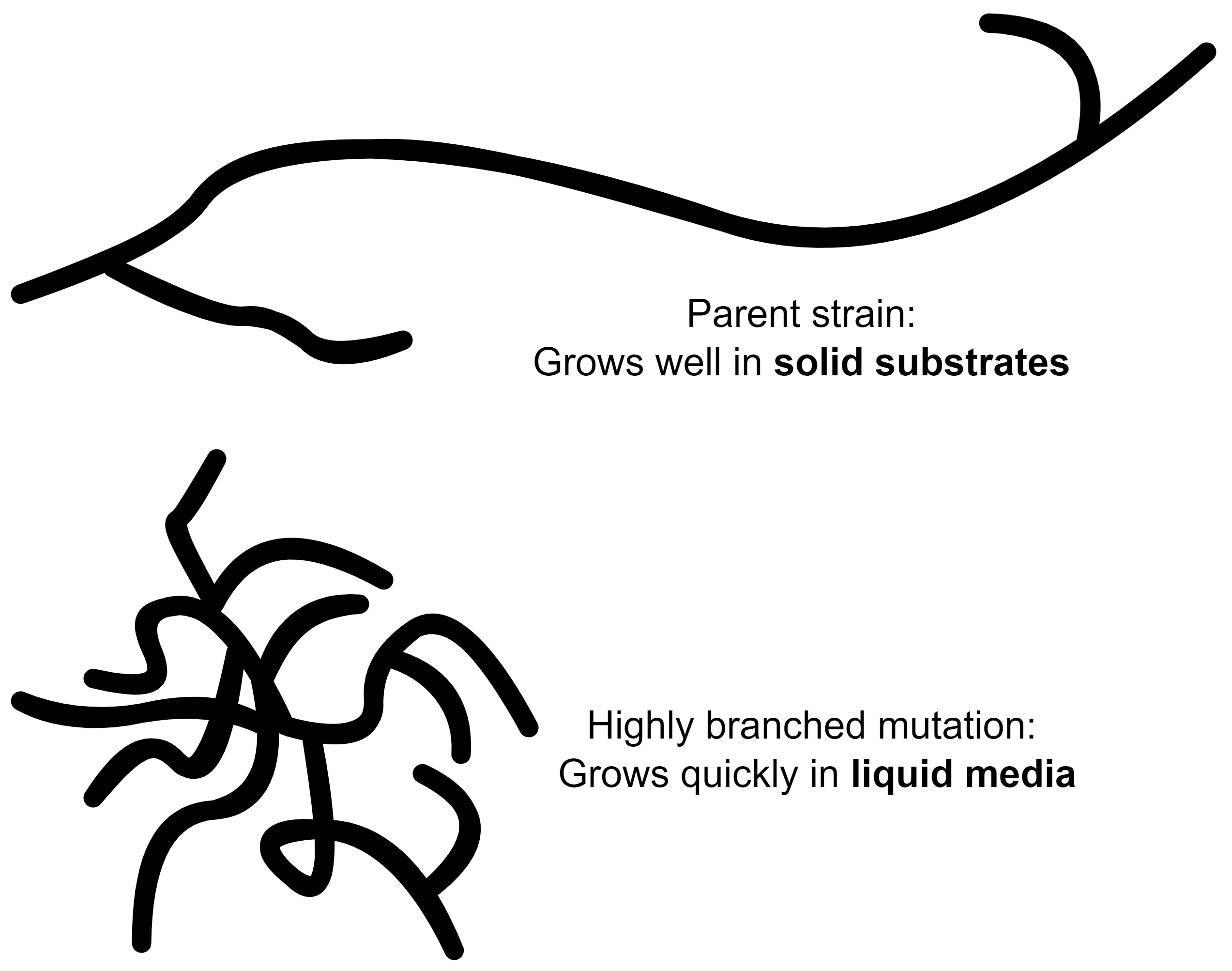

Mutations

Growing a continuous culture over an extended period of time presents an interesting issue: over time, the fungi is susceptible to mutations. Like clockwork, a highly branched mutant of F. venenatum will appear after around 100 generations of growth. The branched mutant grows better than the parent strain in the continuous culture, and will eventually replace it.

This isn’t actually a problem for biomass production, but the branched mutation has an inferior texture to the more linear parent. The goal of Quorn is to simulate meat-like fibres which require linear hyphae.

And so, at around 1000h (6 weeks) of operation, the reactor is shut down to be re-seeded with a new culture. For all practical purposes, this is good enough: resetting the reactor at such long intervals is an insignificant loss in productivity and the operators would need a window to clean and perform maintenance anyways.

Final Form

The biomass broth, after heating to 68°C to remove nucleic acids (as a bonus: proteases are inactivated), is heated again to 90°C to pasteurize and then centrifuged to yield a 20-30% solids paste. To make Quorn products, the biomass has to be mixed with calcium, egg albumin (vegetarian products) or gluten, carrageenan, and alginates (vegan products). The product is finally frozen, which also improves the texture.

What did Quorn achieve?

I’m going to offer a few of my own thoughts and speculation on Quorn, and the future of SCP in general.

Quorn as a Benchmark

When I started researching Quorn, my primary goal was to develop a mass & energy balance of the overall process to serve as a benchmark. The key driver is that Quorn is a commercially successful product that has been implemented at scale and with a continuously operated bioreactor.

As I write, Quorn is pretty much the only commercially viable SCP product that can be a primary source of protein for humans. Other products like Nutritional Yeast, Yeast Extract and Spirullina don’t really count - they’re more like flavouring agents or supplements.

Any new or competing product better be more efficient, taste better, or be cheaper to produce. The Quorn benchmark becomes useful once we start looking at the economics of newer SCP products and technologies like cultivated meat from animal cells.

Although it was difficult to piece together the mass balance, since process details tend to only be available to plant operators and engineers, I could piece together a decent estimate by combining several sources [4-10] and my own assumptions:

Process Efficiency

So how does Quorn compare to traditional proteins? The “efficiency” of a source of protein for consumption can be measured in two ways: caloric and protein conversion efficiency. The caloric conversion efficiency is the ratio of calories output by calorie input (recall: we are adding glucose, a high-calorie feed, to the bioreactor). Similarly, the protein conversion efficiency measures is the ratio of protein output by protein input (animals, like humans, require protein to grow and produce their own protein).

At a high level, we ended up with a bioprocess that is more efficient than animal rearing, cost and nutritionally competitive as a meat substitute, but still more expensive than plant proteins. If we examine the caloric and protein conversion efficiencies of Quorn next to animal proteins [13], we can see that it holds up well enough:

| Product | Caloric Conversion Efficiency | Protein Conversion Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Quorn | 21% | N/D |

| Eggs (Chicken) | 17% | 31% |

| Milk (Dairy Cows) | 17% | 14% |

| Poultry | 13% | 21% |

| Pork | 9% | 9% |

| Beef | 3% | 3% |

The efficiency of Quorn is hampered by the 30% biomass loss at the RNA reduction step - in this table I’ve only considered the centrifuged cake as the consumable end-product. This might be the Achilles’ Heel of all SCP - you can have a microorganism that either grows quickly, or has low nucleic acids - not both. And removing nucleic acids comes at a hefty cost.

Quorn doesn’t really have a protein conversion efficiency because it directly utilizes ammonia, not protein, as a nitrogen source.

Quorn as a Pathway

Having a direct pathway from carbohydrates + ammonia to protein has a lot of neat implications. If plant-based meat substitutes continue to gain traction (and I think they will), the production of plant protein isolates and concentrates is going to yield a lot of waste carbohydrates and starches, which will become dirt cheap. This would make the Quorn process a lucrative pathway to upgrade low-value carbohydrates into protein.

Alternatively, if corn ethanol gets banned due to policy changes, we’re going to have a lot of un-used corn milling and hydrolysing infrastructure. These could easily be adapted into Quorn-type protein production plants.

Taste and Texture Matter

A food products’ organoleptic properties matter a lot in the meat substitute space. Quorn’s success comes in part due to the fact the the hyphal product, after heat treatment and freezing, resembles the fibrous texture of meat.

Fried Quorn nuggets - Source: veggiepattytastetest.com

Fried Quorn nuggets - Source: veggiepattytastetest.com

Quorn as a Miso

I’d love to get my hands on some F. venenatum biomass, centrifuged, without heat-treating to remove RNA. I would take this 20-30% solids biomass and heat treat it myself, keeping the 8-9% nucleic acids, and maybe make a miso or garum out of it, since it would contain plenty of natural 5’-ribonucleotides and glutamates. In theory it would make an umami bomb that doesn’t have the flavour of yeast extracts. At the small amounts I would be consuming, uric acid isn’t a problem: so long as daily consumption is under the WHO recommendation of 2g RNA per day (a tablespoon of this stuff should contain around 0.3g).

Maybe I’ll ask Quorn for some, or make my own. The original patents for this bioprocess have already expired [14] - though it would be difficult to replace Marlow Foods’ 35 years of operating experience.

The Protein Crisis

The original goal at inception, to prevent protein malnutrition, was never really met - because thankfully, and generally speaking - the ‘Protein Crisis’ never happened: agricultural productivity kept up with population growth through the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and beyond. This was mostly due to the Green Revolution consisting of better crop strains, fertilizer use, and the like. SCP could never compete economically with plant proteins.

Space Travel and the Apocalypse

Despite its limitations, Quorn and SCP in general might be viable technologies in either an apocalyptic scenario - or space travel - as part of a larger system of chemical processes and bioreactors used to sustain human life.

Let’s say an asteroid - on par with the one that wiped out the dinosaurs - impacted earth and a dust cloud shut down photosynthesis for decades, worldwide. That, or we bomb ourselves into a nuclear winter. In either scenario, SCP might be good insurance against a world without photosynthesis. Nuclear, geothermal or wind power would be required to fix carbon and SCP bioreactors might be our only food source once stockpiles run dry.

Or, let’s say we want to colonize space. The same process might be viable as part of a life support system that closes the loop on human sustenance: exhaled CO2, water, and excreted feces and urine are directly recycled into food with energy as an input. This is a huge oversimplification, but at least it’s thermodynamically feasible and may require less space or energy than an equivalent plant-based farm. I’ll explore this in a future post.

Conclusion

Quorn was developed in the 1960s - 1980s in a coordinated academic, institutional and industrial effort, and it survived the test of time even as other SCPs like Toprina, Peliko and Pruteen fell short and were discontinued.

As we enter an era in which meat alternatives are front and centre, Quorn occupies a decent niche - I don’t see it going away any time soon. Recent developments in this space tend to focus on a) animal culture lines or b) food-science based approaches.

That being said, biology and engineering have progressed a lot since the 1960s. We have more species and tools at our disposal, we understand genetics more, and our engineering has improved. If a company were to make the same coordinated academic, institutional, and industrial push for a “Quorn 2.0”, I’m sure it would yield a superior product or process. Here’s hoping.

And as I mentioned earlier, the patent on the original process has already expired [14].

Oh, and I can’t get Quorn in Canada. This might be an issue with the CFIA, or the parent company simply hasn’t made the push into the Canadian market. I’ll pick some up the next time I’m in the USA or UK.

References

- Semba, R. D. The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health. ANM 2016, 69 (2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1159/000449175.

- Ritala, A.; Häkkinen, S. T.; Toivari, M.; Wiebe, M. G. Single Cell Protein—State-of-the-Art, Industrial Landscape and Patents 2001–2016. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8, 2009. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02009.

- Trinci, A. P. J. Myco-Protein: A Twenty-Year Overnight Success Story. Mycological Research 1992, 96 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80989-1.

- Finnigan, T. J. A. 13 - Mycoprotein: Origins, Production and Properties. In Handbook of Food Proteins; Phillips, G. O., Williams, P. A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857093639.335.

- Wiebe, M. G. Quorn Myco-Protein - Overview of a Successful Fungal Product. Mycologist 2004, 18 (1), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269915X04001089.

- Solomons, G. L.; Litchfield, J. H. Single Cell Protein. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 1983, 1 (1), 21–58. https://doi.org/10.3109/07388558309082578.

- Wiebe, M. Myco-Protein from Fusarium Venenatum: A Well-Established Product for Human Consumption. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2002, 58 (4), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-002-0931-x.

- Ugalde, U. O.; Castrillo, J. I. Single Cell Proteins from Fungi and Yeasts. In Applied Mycology and Biotechnology; Khachatourians, G. G., Arora, D. K., Eds.; Agriculture and Food Production; Elsevier, 2002; Vol. 2, pp 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1874-5334(02)80008-9.

- Comprehensive Biotechnology. 3: The Practice of Biotechnology: Current Commodity Products, 1st ed.; Blanch, H. W., Moo-Young, M., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford [u.a.] Frankfurt, 1985; Vol. 3.

- Finnigan, T.; Lemon, M.; Allan, B.; Paton, I. Mycoprotein, Life Cycle Analysis and the Food 2030 Challenge. Aspects of Applied Biology 2010, No. No.102, 81–90.

- Johnson, R. J.; Lanaspa, M. A.; Gaucher, E. A. Uric Acid: A Danger Signal from the RNA World That May Have a Role in the Epidemic of Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome and CardioRenal Disease: Evolutionary Considerations. Semin Nephrol 2011, 31 (5), 394–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.08.002.

- Portis Jr, A. R.; Salvucci, M. E. The Discovery of Rubisco Activase – yet Another Story of Serendipity. Photosynthesis Research 2002, 73 (1), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020423802875.

- Shepon, A.; Eshel, G.; Noor, E.; Milo, R. Energy and Protein Feed-to-Food Conversion Efficiencies in the US and Potential Food Security Gains from Dietary Changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11 (10), 105002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/10/105002.

- Naylor, T. W.; Williamson, T.; Trinci, A. P. J.; Robson, G. D.; Wiebe, M. G. Fungal Food. US5980958A, November 9, 1999.

Keith Wong

Keith Wong