Flavourzyme™️ is a trademark name given to a mixture of refined proteolytic enzymes branded by Danish biotech company Novozymes A/S. It’s produced by the submerged fermentation of our friend A. oryzae - in this post we’ll look at what it is, and how it’s made.

What is Flavourzyme?

The modern food processing industry uses proteolytic enzymes everywhere: from accelerating cheese aging, modifying breads, as a flavouring (any time you see “hydrolysed vegetable protein”), processed meats, in detergents… the list goes on and on.

Flavourzyme is a specific mixture of proteolytic enzymes extracted from an Aspergillus oryzae liquid culture. What sets it apart from other industrial proteolytic enzymes is that it contains a cocktail of both endo- and exo-peptidases that can efficiently convert proteins into something with more umami, making it useful for applications requiring the development of flavour [1].

Why does this matter? If a protein is fully decomposed into its constituent amino acids, it tends to taste savoury in the presence of salt - as long as there are sufficient glutamates relative to other amino acids. However, if a protein is only partially decomposed, specific peptides can be extremely bitter: for example, the free amino acids Leucine (Leu) and Phenylalanine (Phe) are slightly bitter (with a tasting threshold of 15-20mM), but their simple dipeptide forms, Leu-Leu and Leu-Phe, are ten times more bitter [2].

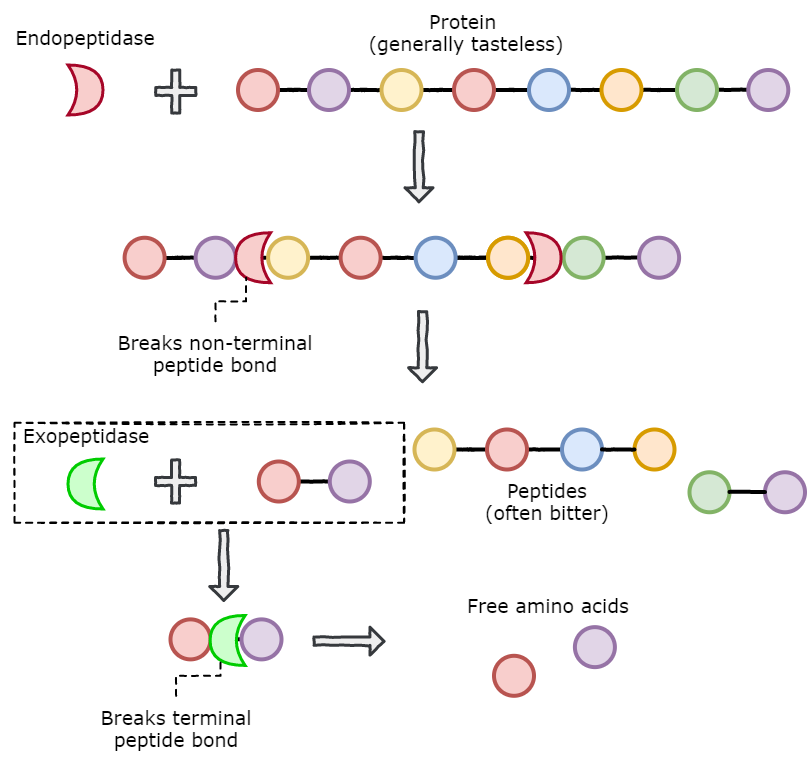

This is why Flavourzyme works well in food applications requiring umami: it contains endopeptidases, which snip peptide bonds in the middle of a peptide chain, as well as exopeptidases, which snip peptide bonds at the terminal ends of a peptide chain.

Simplified diagram of the action of endo- and exo-peptidases. Exopeptidases can cut at the terminal peptide bond, one or two bonds away from the terminal peptide bond, or right in the middle of a dipeptide.

Simplified diagram of the action of endo- and exo-peptidases. Exopeptidases can cut at the terminal peptide bond, one or two bonds away from the terminal peptide bond, or right in the middle of a dipeptide.

Working together in the correct proportion of endopeptidases and exopeptidases, you end up with an enzyme cocktail that yields plenty of amino acids without accumulating any short, bitter peptides.

But wait - how might you make Flavourzyme? And how on earth do you grow A. oryzae in a liquid?

Growing A. oryzae in a liquid - upstream processing

In bioprocess engineering, the process of cultivating a culture is called upstream processing (refining the resultant products is called downstream processing, which we’ll discuss later in this article). For A. oryzae, the process can be a little more involved than growing unicellular organisms such as yeast or bacteria.

Information here is based off a paper from researchers at the University of Denmark, working at the Novozymes A/S Fermentation Pilot Plant, who wanted to develop a mathematical model for enzyme production with A. oryzae in submerged culture [3]. Even though they scrubbed some critical units and sig-figs from their research (for proprietary reasons), it was still enough to piece together details of the process. The process is similar to any other submerged, septic, aerated culture:

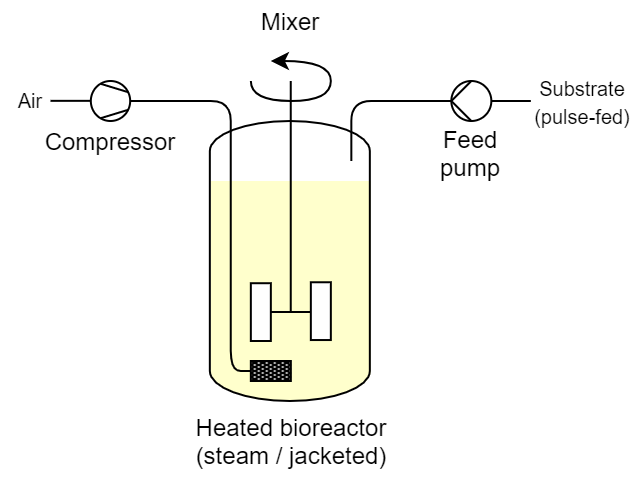

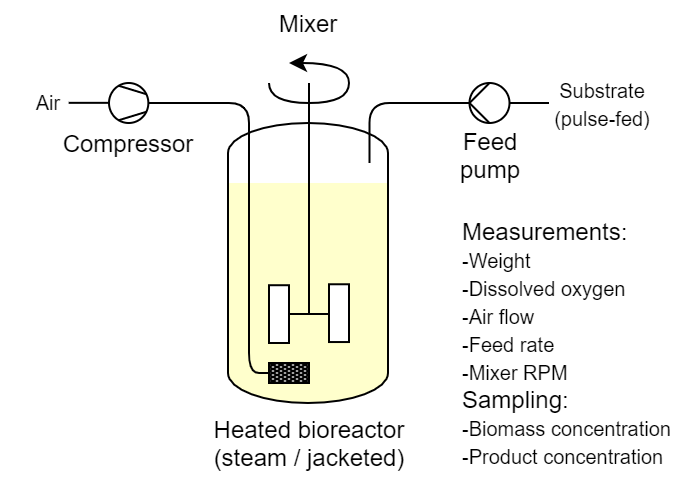

Process diagram of an aerated bioreactor

Process diagram of an aerated bioreactor

A seed train is propagated from a pure culture of A. oryzae and then added to an aerated, stirred bioreactor and allowed to grow. The substrate is typically a mixture of food industry by-products such as starch, wheat bran, corn steep powder, and minerals. Once the culture reaches a certain point, the bioreactor is harvested to yield a crude mixture of enzymes, mycelia, and leftover substrate.

There’s a few quirks to this specific culture method, which applies to some other filamentous fungi fermentations:

1. Use a fed-batch configuration

The bioreactor is primed with substrate and inoculum around 70% full, then additional substrate is slowly dosed in. This is done so that substrate is consumed at basically the same rate that it’s fed into the bioreactor, which keeps glucose in the environment low. As a result, enzyme yields are high by avoiding carbon catabolite repression (which you can read about here and plenty of oxygen is available in the medium to prevent anaerobic metabolism.

2. Filamentous fungi make everything viscous

Filamentous fungi don’t normally grow in a submerged environment. The mycelia will aggregate to form pellets or clumps - which reduces substrate uptake and enzyme secretion. To complicate things, a bioreactor full of filamentous mycelia will make the mixture more and more viscous. This makes stirring harder, and also reduces the ability of air bubbles to mix and for oxygen to dissolve. By necessity, oxygen transfer drops as the mycelia grows.

3. Use a pulsed-paused feeding mode

In addition to using a fed-batch setup, researchers have also found that pulsed-paused feeding, in which feeding of the substrate is turned on/off intermittently in 300s cycles, improves the fungi’s morphology. The rationale is that under starvation considerations, fungal mycelium are known to autolyse (self-digest) older parts of the mycelium network to re-allocate resources to the growing tip. While this mechanism is yet to be studied in detail, it’s been shown that you get better morphology and lower viscosity with pulsed-paused feeding, without sacrificing enzyme productivity [4].

Once the upstream process is finished, you end up with a crude liquid containing fungi, enzymes, spent substrate, and all sorts of metabolites.

Refining the enzymes - downstream processing

In downstream processing, we want to refine out the enzymes only. While I couldn’t find any literature specifically on the downstream processing of flavourzyme, reading textbook on enzymes was enough to cover the basics [5]. Then, a producer of a Flavourzyme-like product on Alibaba just gave me their HACCP flow diagram, so that made things easy. Here’s one example of how it can be done:

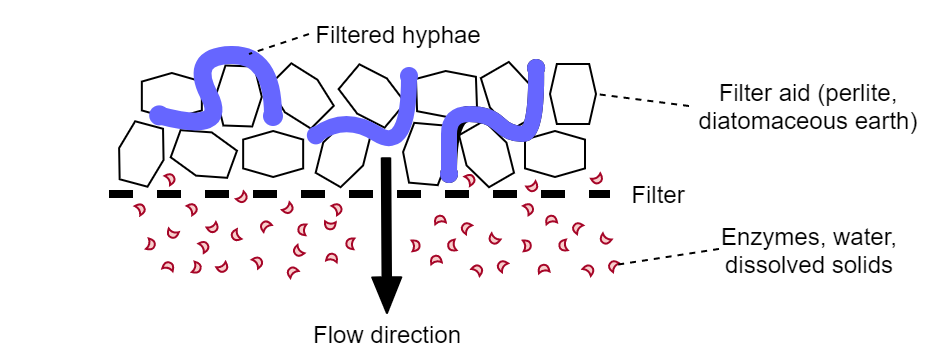

1. Filter Press

The first step is to filter out the mycelia, cell debris, any any other large solids. A filter press is used here with perlite, followed by diatomaceous earth, as a filtering aid. The solid matter is captured in the filter aid and removed as filter cake - leaving behind an enzyme mixture.

Schematic of dead-end filtration with a filter aid - elements not to scale

Schematic of dead-end filtration with a filter aid - elements not to scale

Note that filtration is the first step because we are dealing with extracellular enzymes. If the product was an intracellular enzyme, this step would be preceded by a ‘disruption’ step to break apart cells.

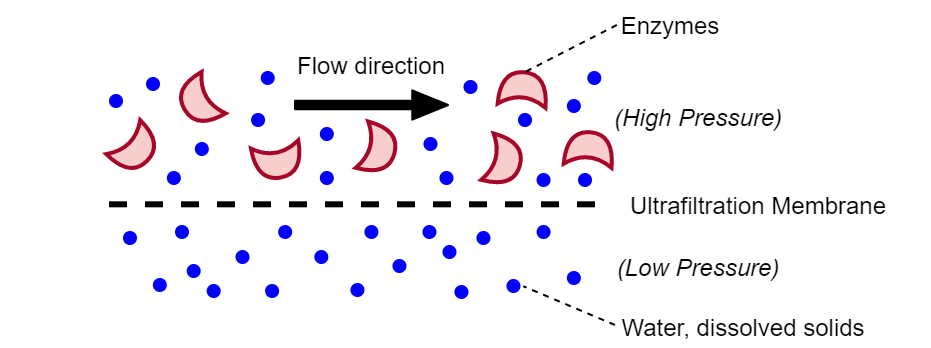

2. Ultrafiltration Concentration

At this point, our enzyme mixture is still at a fairly low concentration. Another type of filtration called ultrafiltration is used to remove water. By passing the liquid across a filter of the appropriate size (in this case, a filter rated around 10kDa), water will permeate through, leaving behind a more concentrated enzyme solution. This can be repeated until the desired concentration is achieved.

Schematic of cross-flow ultrafiltration - elements not to scale

Schematic of cross-flow ultrafiltration - elements not to scale

3. Final Steps

I won’t go into too much detail here, but the final mixture can either be dried by spray-drying with the help of a carrier solid (typically sodium chloride), or packaged as a liquid after passing through a sterilizing filter and adding stabilizers and preservatives.

The Final Product

If everything’s gone well so far we should have a powerful enzyme mixture rated for 500 LAPU/g (one LAPU is the amount of enzyme which hydrolyzes 1 µmol of L-leucine-pnitroanilide per minute - this is one of many enzyme assays for proteolytic enzymes) and 6% w/w of pure enzyme protein, depending on formulation [6]. By comparison, unrefined shoyu koji contains around 0.2% w/w protease [7].

The specific mixture of enzymes identified by researchers is as follows [1]:

- leucine aminopeptidase A

- leucine aminopeptidase 2

- dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- dipeptidyl peptidase 5

- neutral protease 1

- neutral protease 2

- alkaline protease 1

- α-amylase A type 3

Interestingly, α-amylase ends up present as a by-product - I suppose it’s difficult to get A. oryzae not to produce any amylases.

Applications

Novozymes A/S won’t sell to non-commercial or non-institutional end-users, so I had to import an imitation product from Alibaba. Here’s what it looks like:

A Flavourzyme-like product from Alibaba

A Flavourzyme-like product from Alibaba

I plan to use this to make ultra-fast garums - which has been attempted by the guys at Noma, but using pork pancreatic enzymes. Also, credit goes to Preston at Culinary Crush for inspiring this post. A few more applications I will test:

- Accelerated miso / shoyu

- High-fat miso (flavourzyme contains no lipases)

- Accelerated cured tofu

- Home-made Maggi sauce (Red-cap maggi sauce sold in Canada is essentaily wheat gluten + enzymes and additives)

- Hydrolyzing plant-based milks

As a quick side note, Japanese brewers today don’t add pure enzyme mixtures to misos or shoyus - at least not for more expensive types. The reason is unclear, but it has been tested in the past [8].

The other question is, of course, can I brew this at home?

References

-

Merz, M.; Eisele, T.; Berends, P.; Appel, D.; Rabe, S.; Blank, I.; Stressler, T.; Fischer, L. Flavourzyme, an Enzyme Preparation with Industrial Relevance: Automated Nine-Step Purification and Partial Characterization of Eight Enzymes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2015, 63. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01665.

-

Maehashi, K.; Huang, L. Bitter Peptides and Bitter Taste Receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009, 66 (10), 1661–1671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-8755-9.

-

Albaek, M. O.; Gernaey, K. V.; Hansen, M. S.; Stocks, S. M. Modeling Enzyme Production with Aspergillus Oryzae in Pilot Scale Vessels with Different Agitation, Aeration, and Agitator Types. Biotechnol Bioeng 2011, 108 (8), 1828–1840. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.23121.

-

Bhargava, S.; Wenger, K. S.; Marten, M. R. Pulsed Feeding during Fed-Batch Aspergillus Oryzae Fermentation Leads to Improved Oxygen Mass Transfer. Biotechnol Prog 2003, 19 (3), 1091–1094. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp025694p.

-

Enzymes in Industry: Production and Applications, 3rd ed.; Aehle, W., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2007.

-

Flavourzyme 500MG Product Data Sheet - Novozymes A/S. Dated 2017-08-24. Accessed 2021-06-06 from: https://www.ibric.org/myboard/view.php?Board=scicafe000352&filename=0003423_1.pdf&id=3423&fidx=1.

-

Koji Studies, 6th ed.; Hideya, M.; The Brewing Society of Japan: Tokyo, 2018.

-

Mochizuki, T. About the use of enzymes in miso brewing. Journal of the Brewing Society of Japan 1969, 64 (5), 423–430. https://doi.org/10.6013/jbrewsocjapan1915.64.423.

Keith Wong

Keith Wong