Koji generates a considerable amount of heat as it grows - if you’ve ever made koji at home, it’s almost unsettling to feel the warmth of a koji cake. Controlling that heat, along with water content, mixing, and ventilation, is crucial to produce a quality product. In this article, we’ll dive into how temperature and other factors are both controlled and exploited in the koji-making process.

The Temperature Curve

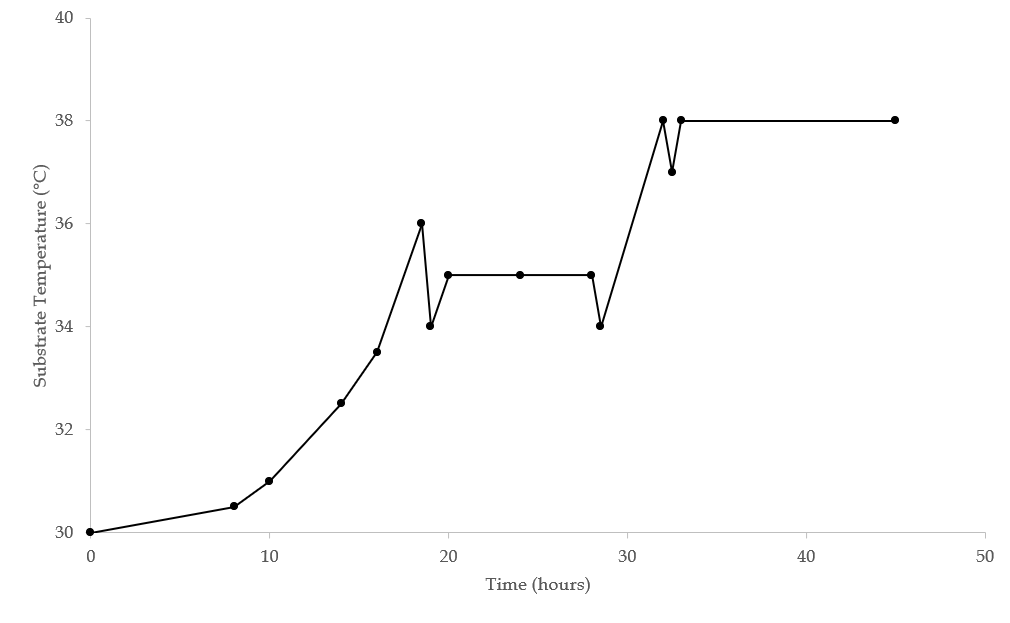

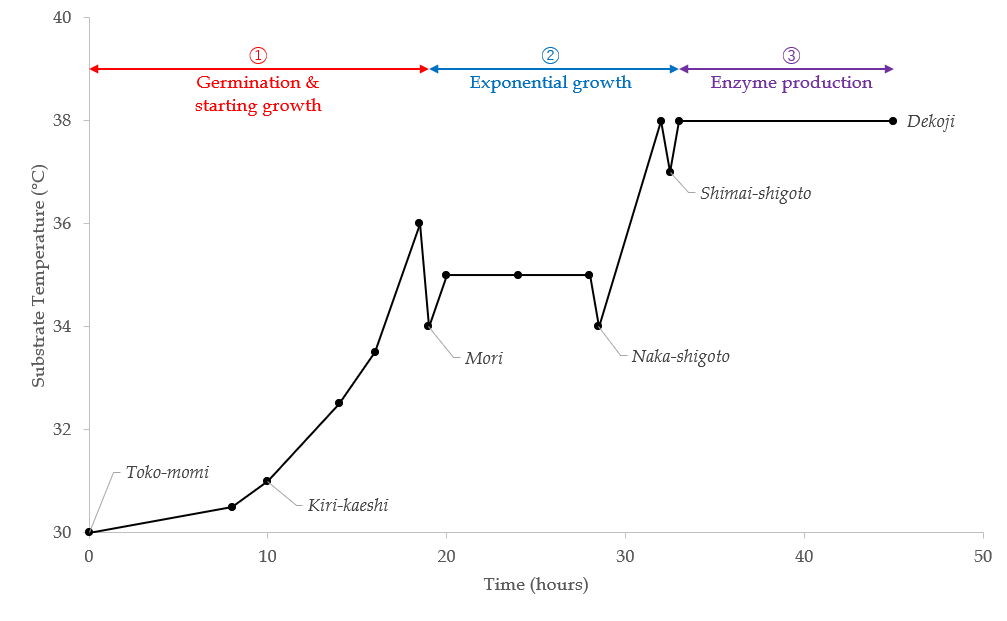

This is an example of a temperature - time curve for sake koji. There are also different curves for mirin, miso, shochu, etc., and for different manufacturing methods, but the key concepts apply for all applications.

Note that this chart refers to the substrate temperature, measured inside the bed of koji, and not the room itself. But why is there such a complicated temperature progression? Can’t we just set a single temperature and walk away? To explain this temperature curve, there are a few things that need to be kept in mind:

- As the koji grows, it will generate heat - approximately 100 kcal/kg for rice koji over its life cycle and 7kcal/kg/hr at its peak (dry weight basis) - and even more for other types of koji

- The optimal temperature for spore germination and growth are different

- The optimal temperature for protease and amylase formation are different

I’ve already described the effects of 2. and 3. in a previous post, but in short: mycelial growth is optimal at 35°C, amylase is favoured between 35°C-40°C, and protease is favoured below 35°C. As for 1., a combination of mixing, ventilation, and adjustments to the bioreactor controls (for machine-made koji) removes heat.

Let’s annotate the temperature-time curve and add the names of the traditional processes to this chart:

The entire process can roughly be broken down into three periods:

- For the first 18-22h, the rice is wrapped up and piled into a mound after inoculation (toko-momi). This is done to keep the pile of rice warm and to retain as much moisture as possible. The koji spores germinate within 6-8 hours, then the pile of koji begins to warm up rapidly as the koji generates its own heat. In the middle of this period at the 10-12h mark, the koji is usually mixed once (kiri-kaeshi) to redistribute moisture between the inside and outside of the pile.

- A step called mori is performed after the initial 18-22h. The pile of rice is distributed into trays, boxes, or spread thinly on another table - depending on the koji-making method. The koji begins to generate a lot of heat at this point, so spreading it out helps dissipate heat and provide air. Two more mixing steps are usually performed at this stage (naka-shigoto and shimai-shigoto).

- In the final phase of growth, the koji is well-established and enzyme production is the most active. At this stage, the temperature must be maintained according to the type of enzymes needed. Once complete, the act of removing the koji from the room is called dekoji and it is subsequently cooled down

A few caveats here:

The graph above is for sake koji only, which finishes at a high temperature to produce a lot of amylase and suppress proteases. I’ve compiled all the temperature curves I have here. Sometimes there will be only two distinct temperature phases if the temperature requirements of periods 2. and 3. are identical.

The exact shape and slope of the curve also depends on the koji-making method (more on methods here). Machine-made koji will have very accurate temperature control, while traditional and manual methods will show a lot more variability and rely on frequent mixing to bring the temperature down.

And lastly, temperature is just one part of the picture. As the koji progresses, two things need to happen:

-

The koji mycelium needs to grow on the surface and interior of each grain

-

The koji needs to have a proper amount of moisture

Mycelia and “Haze”

Japanese brewers have a term called “haze” (pronounced like saké) that describes the state of mycelial growth observed on each grain of koji. The term is further distinguished into two concepts:

- Haze-mawari - how to koji mycelium spreads on a grain’s surface

- Haze-komi - how the koji mycelium penetrates into the grain’s interior

Koji with a high enzyme concentration must have good growth on the surface of the grain, within the centre of the grain, and have the proper moisture content. Brewers have different terms to describe the final product koji’s visible surface and interior growth:

| Visual Indicators | Low interior growth | Good interior growth |

|---|---|---|

| Low surface growth | Haze-ochi (“missed haze”) | Tsuki-haze (“speckled haze”) |

| Good surface growth | Nuri-haze (“painted haze”) | Sou-haze (“total haze”) Baka-haze (“fool’s haze”) |

For most applications, we are aiming to produce sou-haze, which has good surface growth and interior growth to maximize enzyme production. Tsuki-haze is also used in applications requiring good fragrance (such as saké).

It is also possible to achieve good surface growth and interior growth - but still end up with subpar koji. This is called baka-haze or “fool’s haze” - in which mycelial growth is visually good but enzyme yields are comparatively low. This is because the koji’s water content is too high, leading the inhibition of enzyme production via the glucose effect.

So, in order to achieve good mycelial growth and good enzyme yield, moisture needs to be controlled accurately.

Water, the Weight Ratio, and the Glucose Effect

Water has several important functions, and interacts with both temperature, growth, and enzyme production.

Up to a practical limit (i.e. never boil your rice) growth rate is always proportional to water content, and high water content encourages the germination of koji spores.

However, a high water content also inhibits enzyme production. The reason for this is two-fold. Firstly, there is a mechanism called the glucose effect (which is a misnomer, see below). In the presence of abundant glucose, the genes encoding for amylolytic enzymes are switched off. This is a smart adaptation by the microorganism: if there’s already a lot of glucose, why make more enzymes? Secondly, higher levels of moisture increase the activity of enzymes. This is a common effect across all enzymes.

So, in the presence of plenty of water, enzyme activity increases, and the koji’s enzymes end up liberating lots of glucose from the starchy substrate. The glucose is transported back to the koji mycelium, and this triggers the inhibition effect.

Finally, recall that rice koji can generate up to 7kcal/kg/hr during the peak of its growth - meaning that without heat removal, the koji’s temperature can increase by roughly 7°C in a single hour and the whole batch would be cooked in under 2 hours. Thankfully, with adequate ventilation heat can be removed by evaporative cooling (the latent heat of vaporization of water is 578kcal/kg at 34°C). In a single hour, the heat generated by 1kg of koji can be removed by allowing roughly 12g of water to evaporate.

Of course, some of the heat is removed by other mechanisms, like convection and conduction, but it can be shown that the majority of heat removal comes from evaporative cooling. It can also be demonstrated that evaporative cooling is the limiting factor when it comes to air supply for koji growth - more so than oxygen requirements or carbon dioxide removal. More on this in another post.

To keep track of the koji’s moisture content, brewers simply weigh the steamed rice or koji, at whatever stage it’s at, and calculate its weight ratio:

\[\text{Weight ratio (%)}= \frac{ \text{Substrate weight} - \text{Dry rice weight}}{\text{Dry rice weight}} \times 100\%\]Note that this is not exactly the same as total water content, since white rice already contains 10-15% moisture, and the koji’s metabolic processes also produce water. In reference to soaked and steamed substrate, it is also referred to as the water absorption rate or ratio.

The weight ratio is usually measured at these key steps. The values for sake-koji on short-grain rice are provided here - for other applications, see the end of this post.

- After soaking: 28%

- After steaming: 38%

- At inoculation: 33%

- Final product: 17-18%

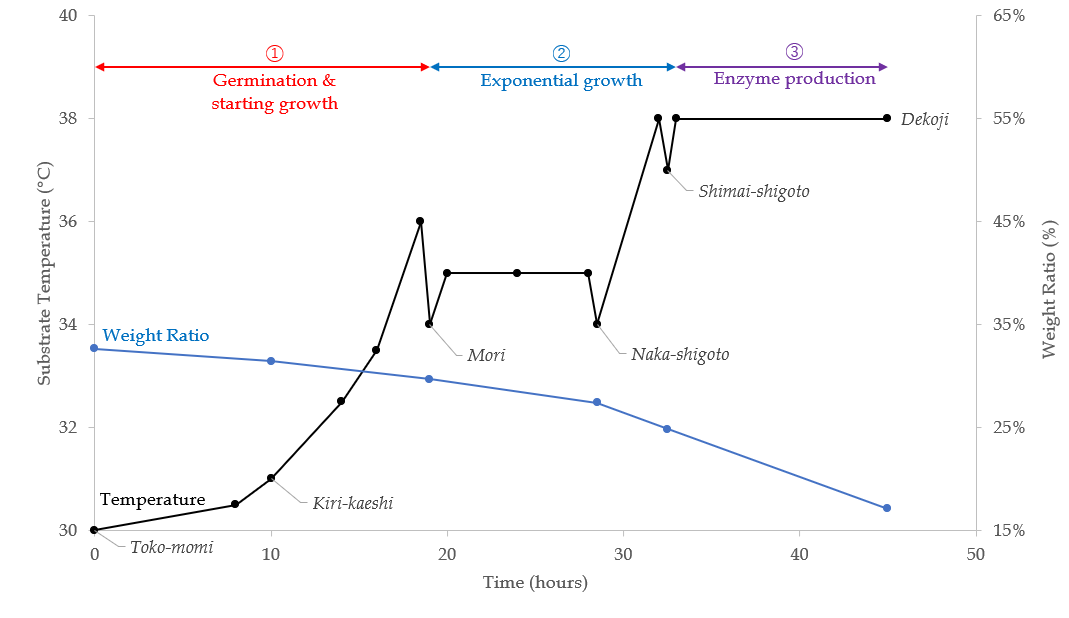

Now let’s add a weight ratio progression to the temperature curve:

Here’s how the water content progresses during each period of growth:

- During germination and the initial growth period, the wrapped-up mound of koji retains a lot of moisture and allows the koji to germinate and grow rapidly. Only a small amount of moisture is lost.

- As the koji’s growth takes off, the heat generated by the koji’s metabolism is removed by evaporative cooling and its weight begins to decline rapidly. Koji producers will slightly reduce the room’s relative humidity and/or increase ventilation to promote cooling.

- During the last phase of growth, the water content is sufficiently low that the koji will produce plenty of enzymes without too much glucose effect. Of course, it cannot be so low that the koji dries out and stop growing entirely.

Chapter IV of Koji Studies sums it up nicely:

It can be said that the mystery of making koji is “to harmonize the drying rate of steamed rice with the growth rate of koji.”

Notes & Conclusions

How much of this matters? Commercial Koji vs Homemade Koji

For home koji makers: just focus on growing koji before worrying about optimal enzyme yields. However, the reference weight ratios and temperatures can be used to help troubleshoot the process.

One of the reasons commercial producers are so meticulous about these parameters is because it affects their product quality and bottom line. Koji takes more time, labour, and energy compared to the application’s non-koji ingredients, so a good enzyme yield is key. For those of us making koji at home, if enzyme yield is low, you can compensate by just using a comparatively high amount of koji. If koji grows too slowly, we can just wait longer.

I also suspect that because commercial producers are dealing with larger amounts of koji overall, their production is less susceptible to moisture loss, and more susceptible to huge swings in temperature (more koji = less surface area per unit volume).

Reference Temperature Curves

I’ve posted all the temperature curves accumulated to date here:

Koji-making temperature curves

It includes curves for sake, miso, mirin, shoyu, and shochu. Again, shoyu and shochu work slightly differently than described in this post but I’ll look at them in detail another time.

Reference Weight Ratios

Here is general table outlining the temperatures and weight ratios for different applications.

| Application | Substrate - Polishing Ratio | After soaking | After steaming | Completion (Dekoji) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sake | Rice - 50-75% | 28-30% | 38-40% | 17-19% |

| Mirin | Rice - 83-90% | 28-30% | 38-40% | 24-28% |

| Miso | Rice - 83-90% Barley - 50-90% (pearled) |

28-30% 28-30% |

36-37% 38-40% |

20% |

| Hatcho miso & Miso-dama |

Soybeans - N/A | 60% | 65% | 20-40% |

| Shochu** | Rice - TBD Barley - TBD |

28-30% 28-30% |

38-42% | 17-22% |

| Shoyu* (water content) |

Soybeans - N/A Wheat - N/A |

60%* 13%* (not soaked) |

58-64%* 4% (after roasting)* |

24-28%* |

*For shoyu, the true water content is shown. It seems brewers prefer to use true water content for shoyu. Some of the shoyu values need to be confirmed. The values for shoyu depend on the soybean to wheat ratio.

**For shochu, some values need to be confirmed. There are additional substrates not listed here. There may also be a difference between the two grades of shochu (continuously distilled 甲類焼酎 and single distilled 乙類焼酎) - to be confirmed.

Glossary of Japanese Terms

Here is a list of Japanese terms pertaining to the koji-making process. This can be used in conjunction with the reference temperature curves. Some terms were not covered in this post - but I’ve explained them briefly here.

| Literal English / Note | Japanese | Romaji / Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate temperature | 品温 | Hin-on |

| Lit. ‘pull in’ - pull steamed substrate into koji room / machine | 引込み | Hiki-komi |

| Lit. ‘cut with spores’ - inoculation | 種切り | Tane-kiri |

| Lit. ‘put on table’ - heaping on table for germination | 床もみ | Toko-momi |

| Lit. ‘sideburns’ - germination, often in reference to temperature | もみ上げ | Momiage |

| Lit. ‘cutting back’ - action of mixing, and also the first mixing step | 切返し | Kiri-kaeshi |

| Lit. ‘peak’ - transfer to lid / box / etc. | 盛り | Mori |

| Lit. ‘maintenance’ - non-specific mixing step | 手入れ | Teire |

| Lit. ‘middle work’ - middle mixing step | 仲仕事 | Naka-shigoto |

| Lit. ‘transhipment’ - shuffling lids or boxes in lid / box method | 積替え | Tsumi-kae |

| Lit. ‘final work’ - last mixing step | 仕舞仕事 | Shimai-shigoto |

| Lit. ‘final transhipment’ | 最高積替え | Saikō-tsumi-kae |

| Lit. ‘final temperature’ - highest reached temperature in sake-koji | 最高温度 | Saikō-ondo |

| Lit. ‘exit koji’ - koji removed from room | 出麹 | De-kōji |

| Young koji - favouring fragrance | 若麹 | Waka-kōji |

| Old koji - favouring enzymes | 老ね麹 | Hine-kōji |

| Conditioning / drying period after dekoji | 枯らし | Karashi |

| Haze - description of koji growth (hiragana sometimes used) | 破精(はぜ) | Haze |

| Surface haze | 破精廻り | Haze-mawari |

| Interior haze | 破精込み | Haze-komi |

| Lit. ‘missed’ haze - low surface & interior growth | 破精落ち | Haze-ochi |

| Lit. ‘painted’ haze - good surface, bad interior growth | ぬりはぜ | Nuri-haze |

| Lit. ‘speckled’ haze - low surface, good interior growth | 突はぜ | Tsuki-haze |

| Lit. ‘total’ haze - good surface, good interior growth | 総はぜ | Sou-haze |

| Lit. ‘fool’ haze - same as sou-haze but too much moisture | ばかはぜ | Baka-haze |

| Rice polishing ratio | 精米歩合 | Seimai buai |

| Water absorption ratio (weight ratio) | 吸水歩合 | Kyūsui buai |

| Soaked rice water absorption ratio (weight ratio) | 浸漬米吸水率 | Shinshimai kyuusui-ritsu |

| Steamed rice water absorption ratio (weight ratio) | 蒸米吸水率 | Mushimai kyuusui-ritsu |

| Dekoji ratio (weight ratio) | 出麹歩合 | De-kōji buai |

References

- Murakami Hideya. Koji Studies - 6th edition. The Brewing Society of Japan: Tokyo, 2018.

- Katsuya Gomi, Regulatory mechanisms for amylolytic gene expression in the koji mold Aspergillus oryzae. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 83:8 (2019), 1385-1401, https://doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2019.1625265

- Shigetoshi Sudo et al., Factors in the formation of haze. Journal of The Brewing Society of Japan, 97:5 (2002), 369-376, https://doi.org/10.6013/jbrewsocjapan1988.97.369

- Kazunari Ito et al., Quantitative evaluation of haze formation of koji and progression of internal haze by drying of koji during koji making. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 124:1 (2017), 62-70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.02.011

- Wisman, A. P et al., Mapping haze-komi on rice koji grains using b-glucuronidase expressing Aspergillus oryzae and mass spectrometry imaging. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 129:3 (2020), 269-301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.09.016

Keith Wong

Keith Wong