The core piece in my incubator is the Inkbird temperature controller. It’s a very simple device: a thermometer measures the temperature of the incubator (or substrate), and when a preprogrammed temperature threshold is crossed, a heater or cooler can be activated. This means the temperature can remain in range via a negative feedback loop. In my set up, I only have a heater, so the temperature can be bounded below, but not above.

One downside with the Inkbird is that it does not record history, so it’s hard to know if a temperature spike occurred. This is important because the heat produced from a fermentation can rise fast enough and kill the organisms. As a data scientist, I also want to have as much data as possible, so we can start to perform data analysis.

I’ve been learning about electronics and sensors as part of a larger project (still a few months away), but I wanted to test what I’ve learned on a tempeh fermentation. The goal was to be able to record the measured temperatures to a local storage. Controlling the incubator temperature would still be done by the Inkbird. However, to measure and record the temperature involved a few pieces of technology:

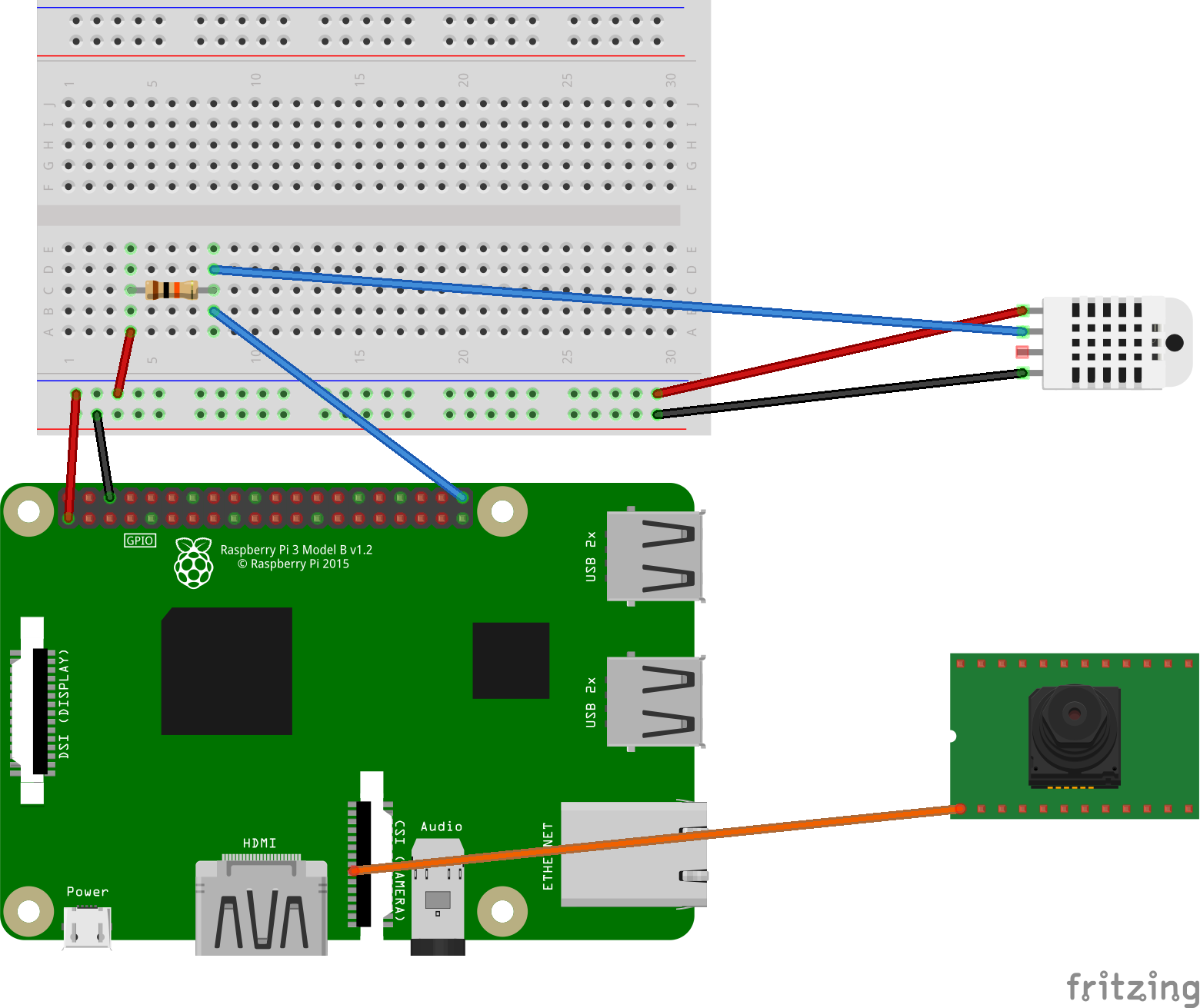

- A Python script running on a RaspberryPi (RPi) records a temperature reading from DHT22 sensor. The sensor was stuck in between two tempeh bags. See appendix for wiring of the RPi and sensors.

- The script publishes the reading to a MQTT server running on the RPi.

- A Node-Red flow, also on the RPi, listens to the specific MQTT topic, and after from some transformations and metadata injections, pushes the data into a SQLite database on the RPi.

Because it was easy and the RPi would already be inside the incubator, I also set up my PiCamera to take a timelapse video of the tempeh evolving.

After the fermentation was done, I used Python to analyze and display the temperature readings, along with the timelapse.

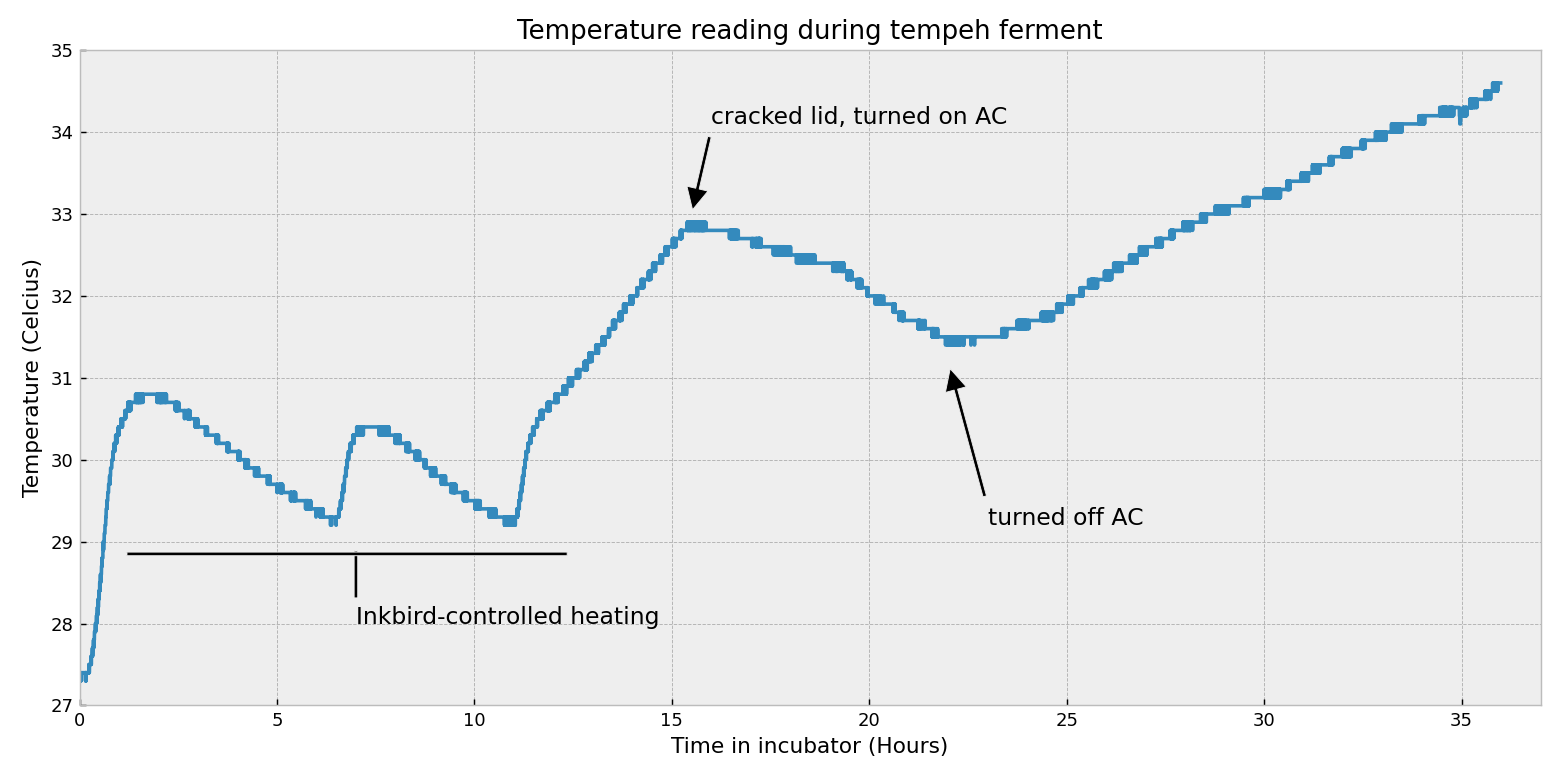

A bit of a rollercoaster ride! Let me add some annotations:

As the fermentation started, the only source of heat was the heater I provided. This caused the oscillation in temperature, as the temperature of the room was lower than the target temperature of 30℃. After ~12h, the fungi, Rhizopus oryzae, had taken hold and started to generate heat. This shot the temperature past 32℃, and would have continued to rise had I not stepped in. I cracked open the lid of the incubator, and turned on the AC in the room. This was enough to reverse the temperature rise. Interestingly, because the interior of the tempeh bag was still warm, and the exterior of the bag was now a few degrees cooler, lots of condensation appeared on the interior of the bag (see gif). As the fungi grew and the temperature fell closer to room temp, the condensation started to disappear. Later, I turned the AC off, and the temperature continued to climb throughout the night. Note that R. oryzae is tolerant of temperatures of up to 42℃, so I didn’t worry about a high temperature killing it during this final stretch. The final tempeh looked great!

White bean and soybean tempeh

White bean and soybean tempeh

What’s next?

This was a proof-of-concept of my data pipelines (also called ETL, or extract-transform-load). With this working, I would like to try to move off the Inkbird altogether, and try using Node-Red and the RPi to trigger the heater.

Wiring

The wiring of my components. Note that a 10kΩ pull-up resistor is present.

The wiring of my components. Note that a 10kΩ pull-up resistor is present.

Cameron Davidson-Pilon

Cameron Davidson-Pilon