A long term goal of mine is to create a plant-based canned anchovy substitute. My market research has shown me that everyone is asking for this! Kidding, of course. The anchovy market is already small, and plant-based anchovies are certainly not the “killer app” of plant-based meats. But anchovies are something that I really miss (I’m vegetarian), an interesting fermentation project, and is a forever unclaimed space in the plant-based market. This article will be an evolving article on what makes the anchovy taste that way it does, and how we can try to replicate that taste with plant-based alternatives.

How canned anchovies are made

There are some interesting videos on Youtube about how traditional anchovies are processed. The process starts with beheading and eviscerating the anchovy fish. Next they are washed in water (sometimes salt water) and then packed in salt and compressed. Here they age for months to years. I suspect that this is not a sterile environment, and there is a fermentation happening here with salt-tolerant bacteria, and some sort of enzymatic action - we’ll discuss this more later. After this salt stage, they are deboned, laid into cans or jars, and filled with olive oil (and maybe vinegar), and sealed. As far as I know, there is not a pasteurization / cooking step after canning - the fact that they are sold refrigerated suggest this as well. So the anchovies purchased by consumers are likely a “living” product (i.e. contains bacteria), a fact that we can take advantage of.

From a food safety point-of-view, the salting stage will halt the growth of most bacteria or fungi. This extreme high-salt, low water-activity environment means that only halophilic microbes can grow. For anchovies, the predominant bacteria is T. halophilus (also found in soy sauce fermenations). This lactic acid bacteria can survive salt environments higher than 15%, but optimal growth is between 6.5% and 10%. So during the salting stage, it’s likely this is the most active bacteria performing some type of fermentation.

Composition of anchovies determines flavour

Proteins, protease and umami

During the salting stage, there is proteolytic (protein cutting) action happening. Initially, while the bacterial populations are low, the proteases from the fish flesh work on itself (an act called autolysis). However, researchers have shown that these proteases have reduced activity and stability when high amounts of salt are added [2]. Really, the majority of proteolytic activity is from the bacteria during the later months of storage. And in fact, the longer the storage, the more proteolytic activity, and the sharper the flavour and loss of firmness. In the video below, Cook’s Illustrated taste tests differently aged anchovies:

It’s the proteolytic action that creates the massive umami bomb that anchovies have. It’s unsurprising that anchovies contains high levels of the amino acid glutamate, the dominant umami flavour compound, which comes from proteases releasing individual amino acids. In fact, glutamic acid, the precursor to glutamate, is the most abundant amino acid in anchovies [4].

To make a plant-based anchovy, we need to find a source that is high in protein and a similar amino acid profile. Soy beans actually satisfies this well. Soy beans are up to 50% protein and have a high level of glutamic acid! Note that anchovies are almost protein and fat, and hence contain little carbohydrates. However, soy does come with carbohydrates, which we’ll address later.

Nucleotides and umami

I’ve read online that anchovies also contain another umami compound, inosinate. This compound works synergistically with glutamates to produce an even stronger umami taste than each compound on its own. Like I said, lots of articles online mention that anchovies contain inosinate, but the academic literature suggests otherwise [3]. In the end, I haven’t come up with a definite answer. To be researched more.

While inosinate typically has non-plant sources, a plant-based compound that also has syngergistic relationship to glutamates is guanylate. Guanylate is present in seaweeds and mushrooms, with very high amounts in shitake mushrooms.

Fatty acids and aromas

Umami isn’t all that makes anchovies delicious. If it was just umami we wanted, we’d be adding yeast extract to our pasta sauces. Anchovies also have a distinct fishy smell that comes from the decomposition of fatty acids found in fish. Raw anchovies predominately contain the ⍵-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), but also some levels of ⍵-3 fatty acid EPA [4]. These ⍵-3 fatty acids are relatively unstable compared to other fatty acids, and breakdown over time into odors that we associate with fish.

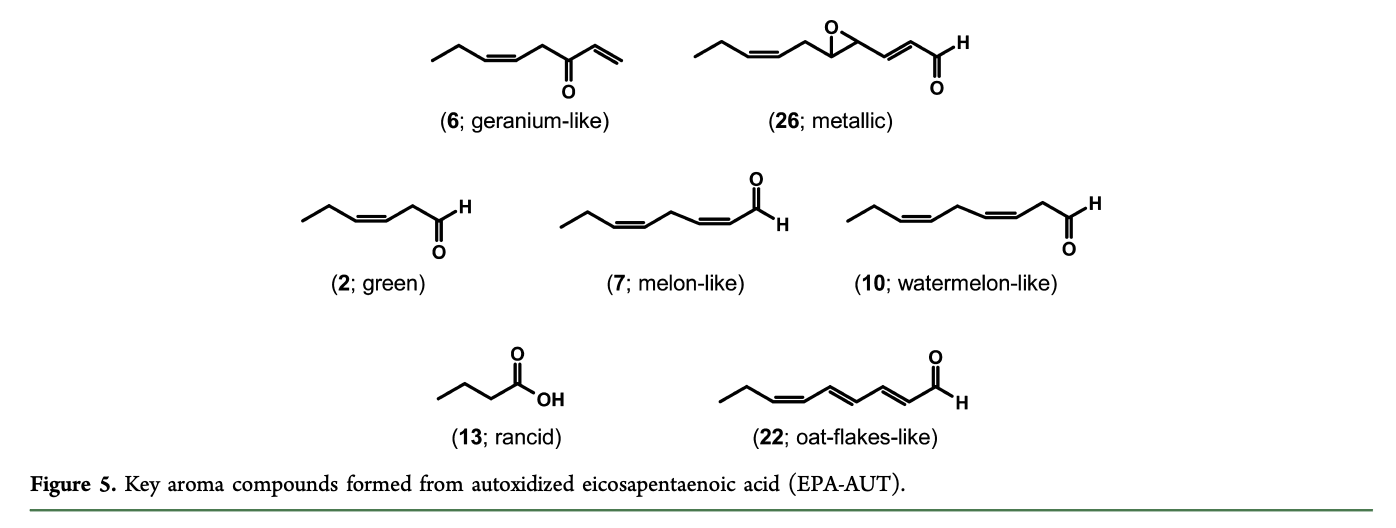

From [5], an overall great article for this project.

From [5], an overall great article for this project.

DHA and EPA are rare to find outside of fish. To make a plant-based product, we need to find a substitute or a plant-based source for DHA and EPA. For a substitute, a common ⍵-3 fatty acid in plants is alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). In fact, it’s found in soybeans. We might expect that the decomposition of ALA could provide a fishy smell, but it’s not nearly as strong as what we want [5]. A plant-based source of DHA and EPA is actually in algae (where do you think fish get their EPA and DHA from). For example, the species Nannochloropsis is high in EPA. Hence why I’m starting my algae cultures - to eventually harvest and use in ferments!

My growing Nannochloropsis - isn’t that green just lovely!

Cultures from Algae Research and Supply.

My growing Nannochloropsis - isn’t that green just lovely!

Cultures from Algae Research and Supply.

Biogenic amines and the funk

Finally, we have the distinct anchovy “funk” that people love or hate. I love it, obviously. This funk is common in most fermented seafood products, like fish sauce and garum. Biogenic amines are produced by the decarboxylation of amino acids. The decarboxylation is caused by decarboxylase, an enzyme produced by the fermenting bacteria.

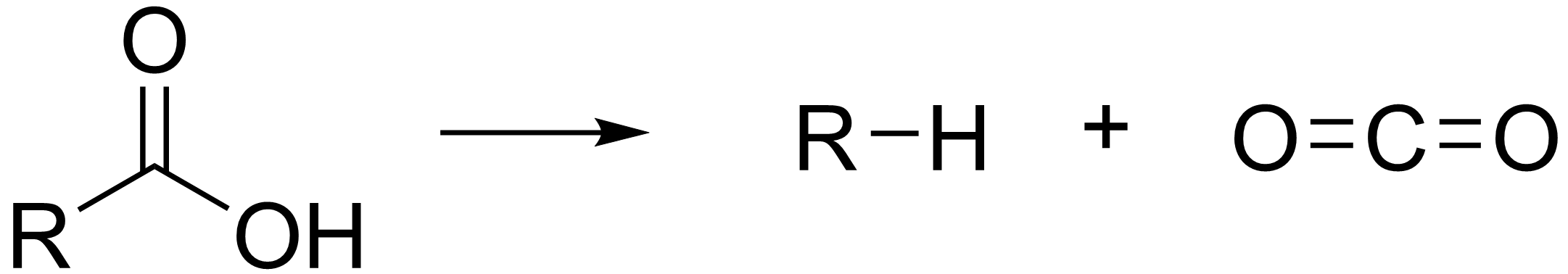

The general decarboxylation reaction. In fermenting anchovies, R is an amino acid. By Edgar181 - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9961806

The general decarboxylation reaction. In fermenting anchovies, R is an amino acid. By Edgar181 - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9961806

Histamine, tyramine, cadaverine, and putrescine are the most common biogenic amines found in fish. In anchovies, histamine is the predominant biogenic amine. Luckily, fermented soybeans contain high levels of histamine as well [6].

Our Recipe

Given the above, we can start to put together what a plant-based anchovy might look like. The amino acids from soybeans, fatty acids from algae (and some extent from soybeans), and nucleotides from seaweed (favoured over mushrooms because seaweed is more “fishy” tasting already). Our source of protease to act on the amino acids can come from koji. And our bacterial starter culture can from a can of anchovies.

Wait - anchovies? Wasn’t the idea to be plant-based? Yes, but we are going to cheat a bit here. Typically with a miso (which this is turning into), a starter “seed” from a previous miso batch is used. We are going to do the same, but our starter seed for this journey is anchovies, which has the bacteria we want. Eventually, we either can use previous batches to seed, or get our hands on a pure colony of T. halophilus.

We also have the problem of carbohydrates. Anchovies are almost completely protein and fat, but our mixtures contains lots of carbs from the soybeans and koji. In later iterations, I want to try using tofu, a pure soy protein product, instead of soybeans.

Trial 1

Recipe

- 200g dried soy beans, soaked overnight and rinsed

- 150g barley koji

- 2 sheets of nori seaweed, ripped up

- 1/2 anchovy fillet from a non-pasteurized can

- 1tsp DHA oil (later will be lysed algae)

- salt

- Autoclave soybeans for 15-20 minutes (add whatever minimal amount of water is needed). Let cool to nearly room temp.

- In food processor, add soy beans, barley koji, sheets of nori, anchovy, and oil.

- Add 10% salt by weight + 1cup water

- Put into fermentation container, cover with saran wrap, and press with weights.

- Let ferment for many months. Not sure how long yet!

The “anchovy mix” after step 2.

The “anchovy mix” after step 2.

References

- Villar M, de Ruiz Holgado AP, Sanchez JJ, Trucco RE, Oliver G. Isolation and characterization of Pediococcus halophilus from salted anchovies (Engraulis anchoita). Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49(3):664‐666.

- Siringan, Patcharin, Nongnuch Raksakulthai, and Jirawat Yongsawatdigul. “Autolytic activity and biochemical characteristics of endogenous proteinases in Indian anchovy (Stolephorus indicus).” Food chemistry 98.4 (2006): 678-684.

- Mouritsen, Ole G., et al. “Flavour of fermented fish, insect, game, and pea sauces: garum revisited.” International journal of gastronomy and food science 9 (2017): 16-28.

- Sankar, T. V., et al. “Chemical composition and nutritional value of anchovy (Stolephorus commersonii) caught from Kerala coast, India.” European journal of experimental biology 3.1 (2013): 85-89.

- Hammer, Michaela, and Peter Schieberle. “Model studies on the key aroma compounds formed by an oxidative degradation of ω-3 fatty acids initiated by either copper (II) ions or lipoxygenase.” Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 61.46 (2013): 10891-10900.

- Doeun D, Davaatseren M, Chung MS. Biogenic amines in foods. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017;26(6):1463‐1474. Published 2017 Dec 13. doi:10.1007/s10068-017-0239-3

Cameron Davidson-Pilon

Cameron Davidson-Pilon